Literature from Saudi Arabia gracing the world stage is rare and what is published does not represent the region fully, Saudi authors say.

Abdul Aziz Alsebail, writer and secretary-general of culture award the King Faisal Prize, says a lack of local professionalism and international ignorance surrounding the kingdom’s literary heritage has rendered Saudi authors mute on the world stage.

Speaking at the ongoing Frankfurt International Book Fair, Alsebail points to a number of titles such as 1988’s Literature of Modern Arabia: An Anthology by Salma Jayyusi and short story collection Voices of Change, with stories and book covers depicting deserts and rolling sand dunes, as providing a limited view of Saudi Arabia.

“What is concerning is the way Saudi Arabia and the surrounding Arabian Peninsula is presented, which is in a very stereotypical way that doesn’t really reflect what is happening today,” he says.

“Publishers seem to emphasise this motif of the desert and in one 1990 short story collection called The Assassination of Light, for example, they also add camels and veiled women as well on the cover.

“This is the atmosphere presented and hopefully with all the modern changes that are happening in Saudi Arabia, this can also change.”

While the works mentioned are more than three decades old, Alsebail says it is important to highlight due to the power of stories when it comes to bridging cultures.

“It is my belief that narratives are probably the best way to export from one culture to another because of its human themes and reflections,” he says.

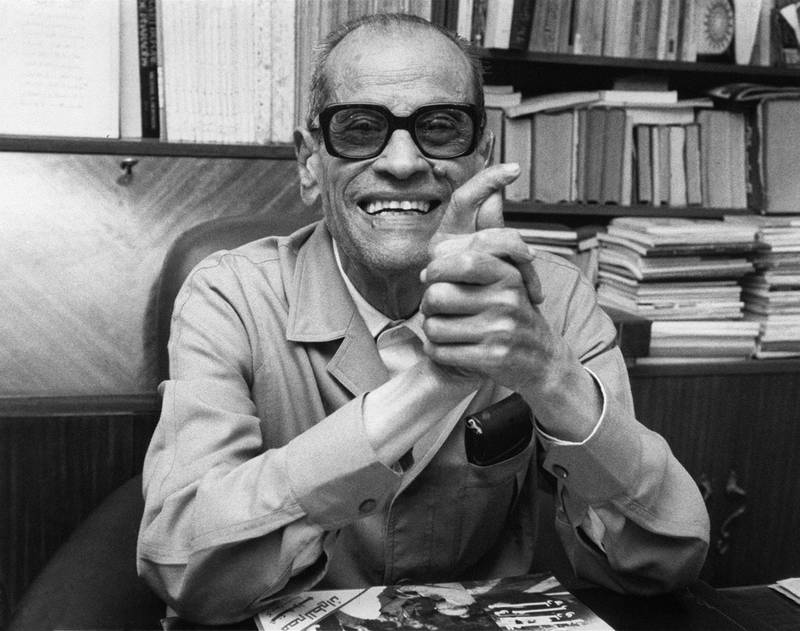

“I mean, it is no coincidence that 90 per cent of Nobel Prize winners for literature, including the Arab world’s sole representative in Naguib Mahfouz from Egypt, are authors of narratives rather than poets for example.”

Initiatives are under way to tackle some of the literary misconceptions surrounding Saudi Arabia, including translation grants and making more pertinent titles by Saudi authors available for translation.

At present, Alsebail says only 200 Saudi works, including novels, short stories and poetry collections, have been translated from Arabic to foreign languages of various quality.

“With respect to some of our Saudi colleagues and great writers, some think that a short story collection translated into English means they have become an international writer, which is absolutely not true,” he says.

“Sometimes these books are translated by someone who is not an expert in the field and released through a third-rate publisher so the book is not really visible.

“The matter is not only about translation, but also about making sure the right books are translated first and to have in mind where it is going to be translated.

“A book that could be accepted in the West is different from one accepted in the East. We are talking about translating one culture to another.”

As part of its participation in the book fair, Saudi Arabia’s Literature, Publishing and Translation Commission, run under the kingdom’s Ministry of Culture, released a market guide of Saudi titles available for translation into German.

The list includes the 2010 International Prize for Arabic Fiction winning Throwing Sparks by Abdo Khal, a crime novel set in Jeddah, and 2018’s Fa’llan by Amal Al Harbi, a psychological novel following the tumultuous life of young Saudi woman Munira.

Moneera Al-Ghadeer, Saudi literary academic and author of 2019’s Desert Voices: Bedouin Women’s Poetry in Saudi Arabia, says market forces should not dictate the type of stories translated from the kingdom.

“Our task as scholars, translators, agents and publishers and also governmental entities and cultural organisations is to work on better initiatives,” she adds.

“For instance why don’t we have agreements with leading publishing houses and university presses to come to our region with a criteria to lift standards and have more literary diversity?

“We cannot just allow the market to dictate and political incentives to select sensational texts or ones promoting stereotypes of the region.”

Alsebail agrees, noting such initiatives could have a greater effect than a more diverse bestsellers list.

“We can create a new type of literature from Arabia, which would go on to change the mainstream thinking and stereotypes of the region,” he says.

“It will be a literature showing a vision of where we are now, and that’s a new and modern Arabia.”

Updated: October 21, 2023, 3:06 AM