At the beginning of 2023, I went to Santa Maddalena, a writers’ retreat run by the Baronessa Beatrice Monti della Corte. It was dark when I arrived at the train station and was driven up a bumpy Tuscan hill. I entered the threshold of the big stone house, and someone in the blur of new faces called out: “Buonasera.” I returned the greeting.

“Parli italiano?” they said—you speak Italian?

“Solo un po’,” I said—just a little. They replied with something I didn’t understand, and I repeated in panic: “Solo un po’!”

Over the next few days, I began to venture further attempts. By some hostly instinct, Beatrice complimented me whenever I most feared I’d botched a phrase. Her assistant Edoardo taught me to say: “Il bicchiere è mezzo pieno o mezzo vuoto,” the glass is half full or half empty—Italians say it both ways around, such that “full” can optimistically come first. The chef Rasika was a sympathetic interlocutor, having herself learned Italian as a second language after emigrating decades ago from Sri Lanka. I still think of Rasika when using idioms she taught me: buona fortuna, sogni d’oro.

At Santa Maddalena I learned to produce snippets of Italian, but I couldn’t hold a lengthy exchange. One morning I told another guest, the translator Matteo Colombo, that I wanted to improve. “We can practice if you like,” Matteo replied in Italian. “You understand, right? I saw you laughing along last evening.” It was true; I understood the dinner table repartee; I also understood Matteo—but when I tried to answer, no words came out.

During the last week of my residency there was a book fair in nearby Florence. I took the train down with Lauren Oyler—who, like me, lives in Berlin and had turned up on a hill in Tuscany at the exact same time—and we discussed whether to attend a panel event. Pro: Our friends would be speaking. Con: They’d be speaking Italian. In the end we went. I understood less than at the dinner table, but more than I’d expected.

In Italian I’d become the laggard I’d avoided being in German.

Leaving the conference room, I wound up speaking to a stranger in Italian. We kept chatting all the way to the bar. It was around fifteen minutes in total. I’d just had my first conversation.

*

At this point I was comfortable in German. I hadn’t known any when I’d moved to Berlin the previous summer, but by winter I was having in-depth discussions and by spring I was reading novels. When you first move to Berlin, people tell you not to “bother too much” with German. This only made me more determined to get fluent as quickly as possible. I found it joyless to treat the local language as a pothole for expats to step around—look, you might trip up at local government appointments, but otherwise there’s no need to dirty your shoe—and I wasn’t sure how people whose own German was bad could so confidently deem the language worthless. My sundry anxieties about living abroad helped to keep me on-task. When I didn’t feel like studying, I thought: what if someone mugs me in German and all I can say is Guten Tag?

There was less incentive to continue with Italian after my return from Tuscany to Berlin. All the Italian expats I knew there spoke at least one other language I was better at, so I persuaded myself that it would be an imposition to ask if we could speak Italian instead. Months passed; I forgot about Italian; I lost all the progress I’d made.

I regretted my idleness when my Italian translator Claudia Durastanti visited Berlin in June. I attended a literary event of hers and Veronica Raimo’s, and went later that week to her joint birthday party with Vincenzo Latronico. All three are terrific writers whom I could only read in translation. Groups of Italians at both events switched to English to include me. I wanted them to be able to stay in Italian; I wanted to read my friends in their own language. But still I hesitated to start. I knew if I’d continued learning after Santa Maddalena, I could have already met my goals by June. Somehow my frustration that I hadn’t worked harder seemed like a reason to continue dawdling. In Italian I’d become the laggard I’d avoided being in German.

The following week, my editor Simone invited me to visit Rome for the September Italian translation launch of my new book. The universe had spoken. My intention was fixed. I had three months to learn Italian.

*

First, I memorized common idioms: non vedo l’ora (“I can’t wait”), acqua in bocca (“my lips are sealed”). I played Italian podcasts while walking, tidying, brushing my teeth. I watched Italian films, no subtitles.

In my second week of properly learning Italian, my friend Chiara invited me to join her Italian book club. I read the assigned short story collection that weekend. My comprehension owed more to my high school French and Spanish than to my more recent exploits in Italian, but I was still elated to make it to the end. I hadn’t had that feeling in English since I was a child—that ‘I just read a whole book’ buzz.

The first meeting of the book club was in a low-lit Kreuzberg bar with mismatched furniture and decorated ceilings. Chiara introduced me to the group, explaining in Italian that I understood but wasn’t quite ready to speak. I’d asked Chiara to say this; I felt like a cuckoo, a nuisance. Still, everyone was far more patient than I had any right to expect. I managed to have a couple of Italian conversations, my first time doing so since the book fair in Florence. I was initially stubborn about not speaking any English—but as the night progressed, my resolve wavered. By the end, I’d spoken 33% Italian, 66% English. It was a better ratio than at Santa Maddalena, but I still had a long way to go.

Between this meeting and the next, I continued marinating in the language. I read Elena Ferrante’s L’amica geniale (My Brilliant Friend) quartet across late July and August. I didn’t use a dictionary. When I came across a new word, I guessed what it meant, and refined my hypothesis on each subsequent appearance. At the start of the first book I caught only the gist; by the end of the fourth, I understood everything. Like a parent, Ferrante taught me her language without the mediating tool of translation.

In late August—six weeks before my Rome trip—the journalist Laura Pezzino interviewed me for the Turin newspaper La Stampa. I’d told my publicist that I wanted to see if I could do the first few questions in Italian. As it transpired, Laura and I spent a whole hour speaking only Italian on Zoom. After we logged off, I could barely believe what had just happened.

Later that week was the next book club meeting. This time I stayed in Italian for the discussion, for the pizza afterwards, for goodbyes before catching my train.

I continued to immerse myself as my trip approached. I read Giuseppi Tomasi di Lampedusa, Natalia Ginzburg and Jhumpa Lahiri, whose marathon decades of learning Italian had emboldened me along my own sprint.

The week before leaving for Rome, I went to the theatre with a university friend. He’s German, the play was in German, but we’d met each other through English. Whenever I speak German around him, I see his bemused expression: When did this feature get installed? My general confidence in the language evaporates under this scrutiny. Besides being awkward, our speaking German is unnecessary; he’s one of those continental Europeans about whom anglophones actually mean it when they say, “His English is better than mine.” But as we sat under a black sky by the river after the play, he offered to switch to German. Hiding theatrically behind my hand, I replied: “Ich mache immer noch Fehler und das ist peinlich.” (“I still make mistakes and that’s embarrassing.”) “Okay, well, English is fine,” he said. I’d been trying to say: please validate that my German doesn’t lacerate your ears. But by direct German social norms, I had just said: the thing I’d in fact just said.

I resolved to be braver in Italy. I would accept all offers to speak Italian, and I wouldn’t beat myself up for not being perfect.

*

Finding an English that works for me as a writer has always felt like language-learning. I didn’t read much Irish literature as a child, so there was a gap between the usages I considered literary and those I heard around me. Should my characters give a lend of something, or give a loan? Am I writing differently to how I talk, or amn’t I? By the time I started reading Irish writers in college, I’d developed a stuffy Anglo-American conglomerate style. Cautiously at first, then with relief, I borrowed from the phraseology of Joyce and Edna O’Brien in order to write like myself.

Most non-Irish people don’t know the difference between Irish English and Irish itself. Irish English is comprehensible to other anglophones—but Irish is a completely separate Celtic language, as distinct from English as Russian is. Fewer than 2% of people in Ireland still use Irish on a daily basis. More prevalent is its impact on our English: we’ve inherited the idioms that our ESL ancestors created by directly translating from Irish. “I’m giving out” means in Irish English that you’re complaining—because “Táim ag taibheart amach” is, word for word, how you’d say it in Irish.

I write fiction in German, though I’ve never shown it to anyone. I want privacy to fumble in the dark. And this August, for the first time, I typed out my first few Italian paragraphs about a hotel receptionist in Rome. She believes she speaks no English, but somehow everyone around her keeps complimenting her command of the language when she’s sure she’s just spoken Italian. The premise, no doubt, came from my having recently read Kafka in German—my second languages bleed into one another as much as they do into my English. Maybe something will come of these fragments. For now I’m just having fun.

*

I started my first morning in Italy with an aimless walk that ended by buying a vegan cornetto at a café. “Che paga, ragazza?” the cashier said. She meant, “What are you paying for?,” but I thought at first she was asking how much. “Un cornetto vegano,” I responded a beat too late, feeling like a stupid child. I ate my pastry at a round metal table outside and eavesdropped on the young women gossiping beside me. How come I understood everything they said, but froze when directly spoken to?

When I write in English, I take a microscope to each word.

That evening’s launch event was in Spazio Sette Libreria, a three-story bookshop with a diamond-patterned marble floor and a ceiling fresco of angels. Just before the event, I met my translator Claudia, whom I hadn’t seen since July. She was talking to my editor Simone; after I’d greeted them, Simone ran something by me in Italian and I responded without thinking about it. Then I saw Claudia’s face doing the same thing my German friend’s does: When did this feature get installed? She gave me a big hug and asked how much of the event I want to do in Italian. My assumption had been: none. It’s one thing privately speaking Italian; it’s another thing to give a public talk on a highly technical topic. Yet I trust Claudia so implicitly that on the spot I changed my mind. We decided that she’d ask me questions in Italian and I’d answer in Italian, but I’d switch to English when I couldn’t find a phrase rather than making the audience wait.

Our conversation went well. I understood Claudia’s questions. Sometimes I switched to English after a few sentences, sometimes I barely switched at all. Claudia translated my English and clarified the dodgier parts of my Italian. She knew me well enough to fill in gaps that not everyone in the audience might. I felt safe. I couldn’t have done it without her.

*

Throughout the rest of the trip I met journalists, podcasters, readers. Most often we did the whole thing in Italian. A few exchanges started in English before shifting to Italian—and then two things happened: my grammar declined, the communication improved. People who’d been hesitant in English smiled and open up. They’d been learning my language far longer than I’d been learning theirs, but their lessons had emphasized grammar over speaking. Monolingual anglophones tend to overestimate the general level of English in Italy. If you travel only speaking English, then a self-selection bias will make the enthusiasts likeliest to engage with you. But when speaking Italian, I met plenty of people who were relieved not to have to use English.

In Rome I encountered the phrase “la nostra lingua,” i.e. “our language.” I’ve never heard the Irish refer to English as “ours” in this way. We speak it, sure—thank you, British colonialism—but so does a quarter of the world. English is too ubiquitous for me to feel that anyone who’s learned it must value my culture specifically. But nobody chooses to study Italian unless they love Italians. While I’m sure there are Italians who don’t appreciate foreigners’ attempts, all I’ve ever encountered is joy. At first I couldn’t believe it. I thought they must, on some level, hate my blunders. Then, at my publisher’s aperitivo, a guest used the Irish word “Gaeltacht” in the middle of an Italian sentence—and suddenly I understood the feeling.

This aperitivo was the moment where I was happiest to have learned Italian. I caught all the jokes; I was seamlessly included. I was the only non-Italian present, and I was proud to keep up without anyone having to translate.

*

When I write in English, I take a microscope to each word. I dialogue with a Martin-Amis-type inner editor who sneers at each prosodic peccato. I’m not sorry to have that lens available to me. There’s value in techie precision. I want my sentences to transmit an unconscious tingle of pleasure; I want my stylistics to feel new. But on my last night in Rome, I opened my novel draft and thought: my first aim is to make myself understood.

After returning to Berlin, I realized I’d left my watch behind in Rome. It’s a butterfingered form of hack symbolism that I’d sooner die than put in a novel: how subtle to have the character plant an object in the place she wishes to stay, and how especially inspired to choose a timepiece, that stopped old symbol of fate. But I’ve not seen the word “orologio” in enough iterations to link it with a sequence of clichés. The Italian for “watch” seems less tightly wound, more free to move how it wants.

__________________________________

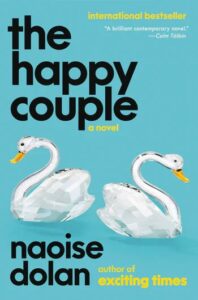

The Happy Couple by Naoise Dolan is available from Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.