While Public Obscenities was chosen as a New York Times Critic’s Pick when it played at Soho Rep earlier this year, many reviewers in DC have found the three-hour length of the play (now at Woolly Mammoth through December 23) to be problematic. A reviewer of Bengali heritage recommended it highly for other Bengalis, as one of the few plays to give audiences an accurate image of Bengali culture. But for non-Bengalis the reviewer recommended it only “if you are looking for a show that challenges you to find meaning and connection.”

I, on the other hand, found the pacing of this play to be a surprise and a welcome relief. I was surprised because there were no melodramatic crises with musical underscoring that manipulated the audience to feel certain emotions at certain times. I found the pacing to be a relief because here was a play in which descendants of formerly colonized and formerly enslaved people of differing cultures experience each other — nay, embrace each other — without going through a white lens first: a play that took its own leisurely time luxuriating in the phenomenon of these people just being themselves with themselves.

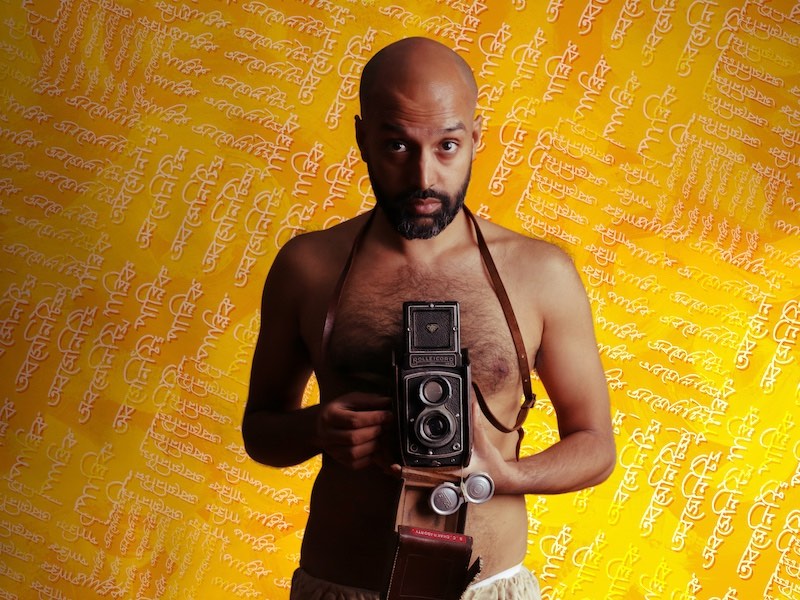

Public Obscenities tells the story of Choton, who visits his aunt and uncle in a home in Kolkata that has been in the family for many years. While there, he documents local LGBTQ life on film for his doctoral thesis. With him is his African American boyfriend Raheem, who is also his director of photography. Raheem’s vocation of noticing and making visual records of things combined with his status as an outsider allows, invites, and leads him to see things that other members of the family miss.

When I spoke by Zoom recently with Public Obscenities playwright and director Shayok Misha Chowdhury, he shared with me in depth his inspirations and aspirations for the work as well as his resistance to making race or sexual orientation a “stumbling block” for the story. I began by asking him directly:

Do you think the play is too long?

Shayok Misha Chowdhury (Misha): I don’t think it’s too long. We really treat the script like a score. The way that the conversation moves, the dialogue moves, the piece is so musical and there’s such a sense of time signature to the piece, that I’m always trying to pay attention to how we keep the audience: making sure that there is this sort of tether pulling them towards the piece. It’s useful feedback that certain audience members felt that they couldn’t access it because of the length. That’s information that I take in to see whether, or not, I am accomplishing what I’m trying to accomplish with the deliberate patience of the piece.

So much of the play for me is about bringing the audience into the experience of being in this home. And so much of what occurs in the play — in terms of what one could consider “conflict” — happens in the unspoken places. Even though it’s a dialogue-driven play, so much of what I’m interested in is what’s happening in the subtlest gesture and the subtlest detail. What happens in the silence at night when one’s partner is asleep and another partner is contending with the rhythms of nighttime?

There’s a particular sort of directorial interest I have in leaning into that kind of spaciousness. For example, I am here [in DC] without my partner Kameron in my apartment right now, and I haven’t spoken to anyone in the last 24 hours. But [in that space] there’s a world, there’s storytelling that’s happening, there’s life that’s happening. That’s the kind of thing that we allow for in cinema often. But that’s harder to do in theater when we’re sort of guiding the audience’s eye without the help of camera editing or zooms and focuses and pans. And so part of my interest was in trying to see how we could guide the audience’s eye inside of theater simply using pace and design.

It’s been a real joy just sitting in the audience and watching audience members have to lean in and engage with the detail of the production. That is intentional on my part.

I understand that the way in which we consume media these days is radically different than it was even 10 years ago. People have certain attention spans and interests in terms of how they want to approach the storytelling that they consume. So it’s not that I don’t understand that it is a long play and that I am asking a lot of the audience in terms of their patience and engagement. But I stand by the expansiveness and the pacing of the piece.

Some folks at Soho Rep called it theater verité, which I kind of appreciate: that it is leaning into a long form, almost documentary-esque sensibility that mimics the rhythms of real life. That’s an experiment that I’m interested in with this particular project.

Would you say more about the pace and design of the show and how they work together in this production?

My collaboration with the design team is a huge part of how I enter into any creative process. It really does matter to me how detailed and inhabited the universe — within which these actors are bringing the story to life — feels.

And it’s a calibration between allowing the actors to fully live inside the intimate womb of that universe that we’ve built on stage, and still share that story outward.

So many of the plays that I’m attracted to as an audience member are plays in which we see unexpected tensions emerge out of the most mundane circumstances. The play begins with Choton and Raheem arriving in Kolkata, and it ends with their departure. I like the experience of watching really closely observed human behavior on stage. Pace is such an important part of that. And design supports the actors’ ability to really lean into that very difficult thing that is naturalism.

There really is a very intense kind of fourth-wall discipline inside of this play. I wanted to give the actors the opportunity to build their experience of the arc of the play without having to worry about the audience. And then I, as an audience proxy, am the one who’s helping the actors to shape their pacing throughout the play from the outside so that they can really live inside of this very detailed home.

And I think that even lighting does so much, and video does so much, and sound does so much in terms of that pace of real life that we’re interested in. The sound of a dog barking while Choton is scrolling through folks’ images on Grindr. Or the way that light helps build the arrival of morning.

To me, those transitions are as much the meat of the play as the scenes themselves.

A camera plays a big part in the plot of the play, with Raheem not only being director of photography for Choton’s PhD project on LGBTQ life in Kokata, but also being someone who photographs family members during his stay. And the audience watches these photographs develop. I wondered while I was watching the play whether you ever studied photography yourself. I mean that old-fashioned kind where you dip the exposed paper into the chemicals and wait for them to develop in a darkroom. And if so, how that affected the pace of the play.

Yeah, yeah. I mean, I have only done that kind. I mean, I am not a photographer by any means, but in my college days, I did take a darkroom photography class. Film photography and the experience of being in the darkroom — the sort of tactility of how photographs come to be — was so fascinating to me and certainly has stuck with me and informed how the play was written. And, yes, the language of a photo developing was a huge part of the dramaturgical conversations of the play.

It does feel like exposing film in some ways is a kind of metaphor for the way that the play operates. I was very interested in the fact that the photographs of Dadu [Choton’s grandfather] that are a central part of how the play unfolds — we only get to experience those photographs through other characters’ reactions to them. And so, for the audience, through these little breadcrumbs, we experience those photos developing in our minds slowly rather than all at once. And that was an experiment that I was interested in.

What does it do when there’s no white person in the show, for the audience that’s watching the show when so much audience coming to see our shows are white?

I was really interested in the comment that you made on the DC Theater Arts review. That analysis was really interesting to me because that’s a way of articulating it that I hadn’t thought about, in that specific kind of language. What was important to me, first of all, is that this is the reality of my life. My Black partner and I go back to Kolkata and there are no white people there. I think that in the stories that I have consumed about interracial or intercultural relationships or about queer relationships, often what it means to be interracial or intercultural is, de facto, a person of color and a white person. And as somebody who’s in an interracial intercultural relationship where the vector of our difference in similarity isn’t mediated through whiteness necessarily, it was important to me to tell a story that was about difficulty and difference and power and history, and those things that we contend with not always being in relationship to whiteness. And it is not as if the ghost of whiteness doesn’t sort of haunt these characters as experiences.

As a younger person, I had the experience of going back to Kolkata and feeling as though there were these sort of easy solves to my feeling of fracturedness as an immigrant person — “Oh, if only I were to be able to love in my mother tongue” or “If only I had not been whisked away to America as a young person, wouldn’t that solve all of my questions about my own body and desires?” I wanted to write a play in which that attempt to romanticize the homeland was complicated, called into question. And I think that’s possible because in this story we are looking at, it’s not as if I started out to write a play about what it means to be in a Black/Bengali relationship. That just is my life, and that’s what I know.

But I think that all of the ways in which Raheem sees the characters in this play are particular to his experience. It’s like the picture of this Bengali family and these Bengali characters that would develop through the eyes of a different viewer would be completely different in many ways. You can frame the play in so many different ways, but to me, it’s a play about what Raheem, because of his particular lived experience as a Black Southern gay man, is able to see in this universe that the characters themselves aren’t able to see.

So, anyone going to go to see this show will have an experience in which everything is going to be explained through a Black man’s consciousness. That’s an interesting thing to happen.

Absolutely. I think that’s a really beautiful way of putting it. I think that really is what it is.

First of all, Raheem is the audience’s way into the play, and why shouldn’t he be? It’s important to me that the particular orientation of this piece asks the audience to view this universe — that might be unfamiliar to us — through the eyes of another character whom we think that we might be sort of impossibly different from. But is that really the case?

I often think about the fact that with those of us who immigrate to this country, there’s an assumption that we assimilate into whiteness. But I wonder. What is it that we assimilate into? There is an Americanness that I have sort of learned: America is a Black country. So, the vernacular that I speak, is it — am I — speaking white? I think that there’s just a sort of assumption that the blank slate of American experience is whiteness.

Those are the questions that I’m interested in, and I love that way of framing it.

I was moved by how quickly and warmly Raheem was embraced by Choton’s family

And I know that that’s a rare and unique experience that is true to my life. So, I just wanted to honor that. It feels like there was a pressure early on to make the fact of Raheem’s Blackness or the fact of this couple’s queerness a sort of stumbling block for the story of the play. And that’s a pressure that I think the culture is often asking of queer storytelling. But I was adamant with myself that I was like, no, let me try and write from my own actual experience and see what other stories might bubble up from that experience.

The play is dedicated to Kameron, Mama and Mami, and then the P 544 family. The dedication felt to me like a valentine or tender love note. Could you talk a little bit about that dedication?

In Bengali, we have a particular word for every different family relationship. “Mama” is mother’s brother, and “Mami” is mother’s brother’s wife. My Mama and his wife (my Mami) were the stewards of the joint family home, the address of which is P544 R— Road. That house, which is sort of the hearth around which I grew up, is an inspiration for the play and functions like a character in the play itself. My partner Kameron is Black and is a visual artist. He and I have traveled back to Kolkata many times. It is the experience of the two of us navigating that household in that universe that is the context from which the world of the play emerges for me.

The dedication comes from the fact that my uncle (my Mama) had shared this dream with me. I recorded a little voice memo of him telling me about this dream he’d had in which he was sitting in a movie theater and seeing this movie.

My Mama passed away as the play closed at Soho Rep. He was in the hospital in India, looking at production photos of the play and knowing that his dream was being transformed into something else by all these other folks and oceans away from him.

I wanted to write a play about who gets to be an artist and who we see and who we don’t see, and visibility and invisibility. I wanted to contend with the fact that he had gifted me this dream as a kind of a mandate. He was like, “You’re an artist. Go make something of my dream.” I was interested in that moment more than the content of the dream itself.

(This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.)

Running Time: Two hours and 55 minutes with an intermission.

Public Obscenities plays through December 23, 2023, Tuesdays through Sundays, at Woolly Mammoth Theater Company, 641 D Street NW, Washington, DC. Tickets (starting at $25 for patrons under 30) may be purchased online, by phone at 202-393-3939 (Wednesday–Sunday, 12:00–6:00 p.m.), by email ([email protected]), or in person at the Sales Office at 641 D Street NW, Washington, DC (Wednesday–Sunday, 12:00–6:00 p.m.).

The program for Public Obscenities is online here.

COVID Safety: Mask-required performances are December 14 at 7:30 pm and December 23 at 2 pm. For all other performances, masks are encouraged but optional in all public spaces at Woolly Mammoth Theatre Company. Woolly’s full COVID policy is available here.

SEE ALSO:

Queer romance set in India coming to Woolly Mammoth as ‘Public Obscenities’ (news story, November 2, 2023)

‘Public Obscenities’ unpacks private desires at Woolly Mammoth (review by D.R. Lewis, November 20, 2023)