In the unequal distribution of birds and other species, ecologists are tracing the impact of bigoted urban policies adopted decades ago.

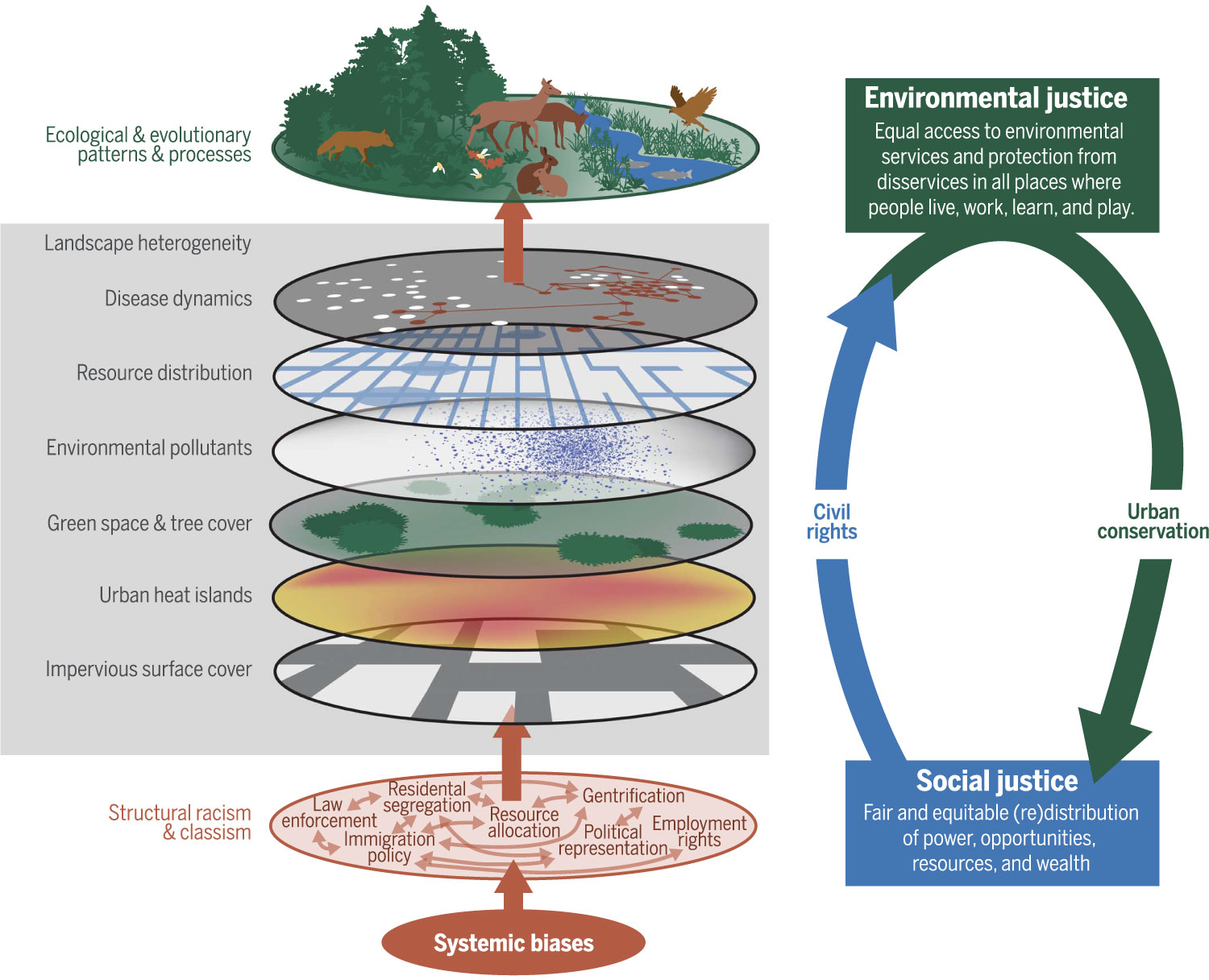

At a meeting of urban wildlife researchers in Washington, D.C., in June, one diagram made it into so many PowerPoint presentations that its recurrence became a running joke. The subject, though, was serious: The diagram illustrated the links between structural racism, pernicious landscape features such as urban heat islands, and impacts to biodiversity, and it came from a study published in the fall of 2020 in the journal Science.

That study was “Ecological and evolutionary consequences of systemic racism in urban environments,” led by Christopher J. Schell, an ecologist at the University of California, Berkeley. It synthesized what a handful of urban ecologists around the country had begun demonstrating: that patterns of bigotry and inequality affect how other species experience life in cities.

Dr. Schell, who is Black and from Los Angeles, said he grew up with an understanding that “there is a ton of heterogeneity that exists in a city, and it’s not by accident that it’s that way.” Those variations could include the numbers of parks and street trees in different neighborhoods, whether a highway or rail line ripped through a community or whether an oil refinery spewed toxins into the air.

Racism and the Environment

A diagram from the journal Science illustrates the links between structural racism, urban landscape features and their impacts on biodiversity.

#g-diagram-box ,

#g-diagram-box .g-artboard {

margin:0 auto;

}

#g-diagram-box p {

margin:0;

}

#g-diagram-box .g-aiAbs {

position:absolute;

}

#g-diagram-box .g-aiImg {

position:absolute;

top:0;

display:block;

width:100% !important;

}

#g-diagram-box .g-aiSymbol {

position: absolute;

box-sizing: border-box;

}

#g-diagram-box .g-aiPointText p { white-space: nowrap; }

#g-diagram-750 {

position:relative;

overflow:hidden;

}

#g-diagram-600 {

position:relative;

overflow:hidden;

}

#g-diagram-335 {

position:relative;

overflow:hidden;

}

As a discipline, urban ecology is only about a quarter-century old, and until very recently its practitioners tended to treat cities mainly as a contrast to rural areas, without considering the wild disparities between and within cities. Dr. Schell wanted to show that urban heterogeneity in turn “is driven by systemic inequities,” he said, like “oppression, residential segregation, gentrification and displacement, unjust zoning laws, homelessness, so on, so on, so on.” Those issues don’t only impact people, he added: “How we operate influences the rest of the natural world as well as the social world.”

Over the past few years, a widening group of urban ecologists has been fanning out to study the overlap between environmental justice and biodiversity conservation, fields that had previously tended to keep to their own corners. Dr. Schell said that, in his lab, researchers “oftentimes do our own version of ‘six degrees of separation from Kevin Bacon’” to show how human actions ripple out to wildlife.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

We are confirming your access to this article, this will take just a moment. However, if you are using Reader mode please log in, subscribe, or exit Reader mode since we are unable to verify access in that state.

Confirming article access.

If you are a subscriber, please log in.