A new computer model to predict the weather built by Google and powered by artificial intelligence consistently outperforms and is many times faster than government models that have existed for decades and involved hundreds of millions of dollars in investment, according to a study published Tuesday.

The Google model even displayed accuracy superior to the “European model,” widely considered the gold standard.

The study, published in the journal Science, showed the AI model to be more accurate for forecasts of both day-to-day weather and extreme events, such as hurricanes and intense heat and cold.

Its stellar performance and promising results from other AI models like it may signify the start of a new era for weather prediction, although experts say it doesn’t mean AI is ready to replace all traditional forecasting methods.

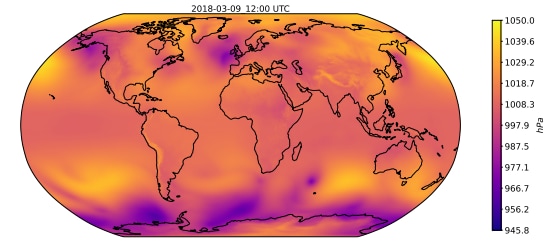

Google DeepMind’s AI model, named “GraphCast,” was trained on nearly 40 years of historical data and can make a 10-day forecast at six-hour intervals for locations spread around the globe in less than a minute on a computer the size of a small box. It takes a traditional model an hour or more on a supercomputer the size of a school bus to accomplish the same feat. GraphCast was more accurate than the European model on more than 90 percent of the weather variables evaluated.

The study’s results are similar to those in an academic article published in August to the online database arXiv.

“To be competitive with arguably the best global prediction system, if not outperforming it, is astonishing,” Aaron Hill, lead developer of Colorado State University’s machine learning prediction system, said in an email. “You can safely add GraphCast to a growing list of AI-based weather prediction models that should see continued evaluation for their application in industry, research and operational forecasting.”

AI weather models have drawn increasing attention from government weather agencies because of their speed, efficiency and potential cost savings.

Traditional weather models, such as “the European” operated by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) in Reading, United Kingdom and “the American” by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, make forecasts based on complex mathematical equations. Such models underpin forecasts and lifesaving warnings worldwide, but are expensive to run because they require tremendous amounts of computing power.

AI models use a different approach. They are first trained to recognize patterns in vast amounts of historical weather data, then generate forecasts by ingesting current conditions and applying what they learned from the historical patterns. The process is much less computationally intensive and can be completed in minutes or even seconds on much smaller computers.

The ability to learn from the growing archives of past weather data is a key advantage of AI models. “This has potential to improve forecast accuracy by capturing patterns and scales in the data which are not easily represented in explicit equations,” the authors, who developed the model, wrote in the study.

GraphCast’s performance was evaluated against the European model not only for individual weather variables such as temperature, wind and pressure, but also in forecasting extreme events including tropical cyclones, atmospheric rivers, heat waves and cold snaps.

Researchers have expressed concerns about the ability of AI to accurately forecast extreme weather, in part because there are relatively few such events to learn from in the past. Yet GraphCast reduced cyclone forecast track errors by around 10 to 15 miles at a lead time of two to four days, improved forecasts of water vapor associated with atmospheric rivers by 10 to 25 percent, and provided more precise forecasts of extreme heat and cold five to 10 days ahead of time.

“Conventional wisdom would say using [AI] might not do as well on the rare, unusual stuff. But it did seem to do well on that,” Peter Battaglia, research director at Google DeepMind and one of the study’s co-authors, said in an interview. “We think this also points to the fact that the model is capturing something more fundamental about how the weather actually evolves in time rather than just looking for more superficial patterns in the data.”

Hill cautions that while the study “reinforces the notion that for most events, skillful forecasts can be made,” the results don’t eliminate questions about AI’s effectiveness at predicting extreme events. “The study describes some rather broad, aggregate statistics of extreme weather forecast skill, which signals how well the model performs over many events, but doesn’t necessarily provide details on how it performs on any one single extreme event,” he said.

Other challenges remain before AI models like GraphCast can be reliably used in operational forecasting. For example, due to limitations in training data and engineering constraints, global AI models aren’t yet able to generate forecasts for as many parameters or as granular as those from traditional models. That makes the AI models less useful for predicting smaller-scale phenomena, such as thunderstorms and flash flooding, or bigger weather systems that can produce large differences in precipitation amounts over small distances.

Meteorologists must also learn to trust AI models whose inner workings are less transparent than traditional ones.

“A key role of forecasters is to interpret and communicate information to partners, a task made more challenging by the lack of tools to determine why an AI model makes the forecast that it does,” Jacob Radford, data visualization researcher at the Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere at Colorado State University, said in an email. “These models are still in their infancy and trust still needs to be developed in both the research and forecaster community before operational use is considered.”

Most experts, including the study’s authors, agree that traditional models aren’t about to be replaced by AI models, which still depend on traditional models to supply training data and to generate the current conditions they use as a starting point to make a forecast.

“Our approach should not be regarded as a replacement for traditional weather forecasting methods, which have been developed for decades, rigorously tested in many real-world contexts, and offer many features we have not yet explored,” the authors wrote. “Rather our work should be interpreted as evidence that [AI weather prediction] is able to meet the challenges of real world forecasting problems, and has potential to complement and improve the current best methods.”

Recent advances in AI weather forecasting

Big Tech companies including Google, Microsoft, Nvidia and China-based Huawei have made rapid advances in AI weather modeling in the last two years. All four companies have published academic articles claiming their global AI models perform at least as well as the European model. Those claims were recently corroborated by scientists at the ECMWF.

In September, AI models developed by Google, Nvidia and Huawei nailed the track forecast for Hurricane Lee a week in advance. Lee rapidly intensified into a Category 5 hurricane in the Atlantic Ocean east of the Caribbean, then weakened before ultimately making landfall in Nova Scotia at a strength equivalent to a tropical storm.

The ECMWF had begun publishing forecasts from all three models on its website just a day after Lee first developed into a tropical storm. The NOAA-affiliated Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere at Colorado State University will launch a similar website by early December, according to Radford.

Meanwhile, the U.K. Met Office recently announced a collaboration with researchers at The Alan Turing Institute in Britain to develop AI forecast models “to improve the forecasting of some extreme weather events, such as exceptional rainfall or impactful thunderstorms, with even greater accuracy,” the Met Office said in a news release.

And earlier this month, Google announced another AI model that can make more localized forecasts of precipitation, temperature and other parameters out to 24 hours using direct observations from weather sensors as a starting point.

Besides modeling, AI is also being used to enhance the communication and interpretation of weather forecasts. NOAA announced last month that it was using AI to automate translation of weather forecasts into Spanish and Chinese, and that additional languages would follow, while the private weather firm Tomorrow.io has developed an AI assistant named “Gale” to help business clients interpret weather forecasts for specific use cases.