- Courtesy Of Charles Maclean

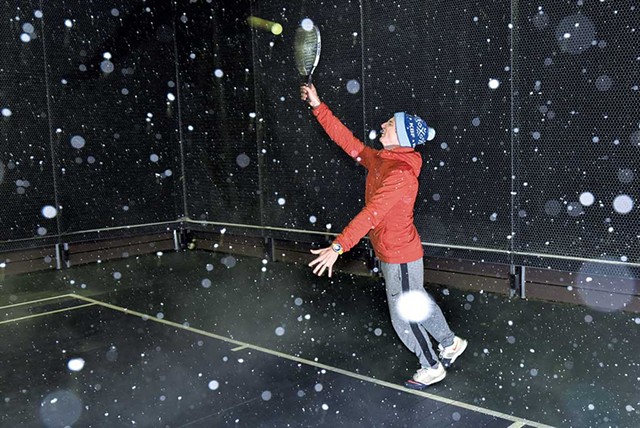

- Max Dangerfield playing platform tennis on a private court in New Haven

Oh, November. Your winds blow until trees stand naked against gray skies. Fields lie frozen. Night slowly encroaches upon day until, finally, on the 30th, it snuffs out the sun at 4:14 in the afternoon.

Yet for 225 people in the greater Burlington area, the month sparks joy. November 1 marks the official start of Burlington Tennis Club’s platform tennis season. This 95-year-old sport invented for winter takes players outside in the cold, in the snow and often after dark to whack a rubber ball across a net. And at BTC in South Burlington, they clamber for court time.

“You’re playing a sport; you’re getting exercise; you’re socializing. It checks a lot of boxes, especially in the winter in Vermont,” said Stefanie Waite, who gives up her gym membership for the season to play “paddle,” as most people call it, three or four times a week.

“And then there’s always the importance of the postgame beer in the shed,” said her husband, Miles Waite. Like most players, he salutes the social aspect of the game. “Drinking beer afterwards is part of the whole process.”

Played on a screened-in, lighted platform, the sport is a doubles game that combines elements of tennis, squash and racquetball. Hinged flaps along the perimeter of the raised deck allow snow to be shoveled off. Heaters underneath melt what’s left, and grit on the surface provides additional traction — and significant wear on shoes.

A thin flocking covers the rubber balls. The paddles are shorter, more circular and a bit heavier than tennis rackets. The heads are made of compressed foam — dotted with holes to help the paddle move through the air — and covered with coarse grit to better control the ball.

Wilson paddles come with a patented bottle opener on the base of the handle “for those who want to drink responsibly,” the company says.

The game’s small court — 20 by 44 feet, roughly one-third the size of a tennis court — allows conversation between all four players. And its rules keep play moving. Players get one serve. They play balls off the screen, and, unlike in tennis, they play the “lets,” the balls that graze the net but land in the right spot — the service box — on the other side.

It’s a mental game, according to BTC tennis director and membership manager Errol Nattrass. Points are typically won when an opponent makes a mistake, he said, adding, “With tennis, it’s much easier to hit a winner.” If an opponent hits a hard shot, a tennis player’s instinct is to immediately cut it off, whereas “a good platform player will let the ball bounce, hit the fence and, before it lands again, put it back into play,” Nattrass explained.

- Courtesy Of Errol Nattrass

- Annie Ode

Platform tennis calls for less aggression and more patience. The so-called chess game of racket sports, its skilled players send the ball back and forth a long time before anyone scores. That’s called a long point. “So the better you are, the warmer it is,” said Courtia Worth, a former platform tennis pro who lives part time in Dorset.

Low temps don’t hamper play, but warm weather makes the ball too bouncy. “You can play when it’s, like, zero degrees, as long as there’s no wind,” said Stefanie Waite, half of the undefeated BTC women’s championship team. Wind wreaks havoc with the ball. “But if it’s not windy and it’s super cold,” Waite said, “you start shedding layers just like you do when you’re cross-country skiing.”

Camille Thoman captured the spirit of the sport in her 2014 documentary The Longest Game, which followed a group of men, nearly all in their eighties, who played their “one o’clock game” every day at the Dorset Field Club. “We play it because a) we like it, No. 1,” David Bumgardner says in the film. “No. 2, winters in Vermont can be like 10 pounds of ham for two people — it’s forever.”

The sport is played predominantly in the U.S. and mostly in colder climates, said Ann Sheedy, executive director of the American Platform Tennis Association, the nonprofit organization that governs the game. However, pockets of players are popping up in southern states, where courts are ground level because they don’t need heaters.

Years ago, there were a few wooden courts in Europe, Sheedy said. Walter Stoessel, the U.S. ambassador to Poland during the Cold War, had one or two courts built behind the embassy in Warsaw, Sheedy said. When he was transferred to Moscow, Stoessel built a court there, then arranged tournaments between the two embassies.

COVID-19 boosted the game’s popularity around the country. BTC’s platform tennis memberships “shot up,” Nattrass said, “and then people just remained in the sport.”

The club, which acquired its first court about 30 years ago, installed a third in 2021. Clubs in Norwich and Quechee also have platform tennis courts, and a faction has been working to bring the game to Stowe. At least two Vermonters are in the American Platform Tennis Association Hall of Fame: Bill Childs of Dorset, who has won 23 national senior titles, and the late 14-time national senior champion Edwina “Winnie” Worth Hatch, Courtia Worth’s sister, who split her time between Dorset and Long Island.

Platform tennis was born in Scarsdale, N.Y., in 1928, when neighbors Jimmy Cogswell and Fess Blanchard were looking for a winter sport close to home. They built a wooden platform on Cogswell’s property for deck tennis, badminton and volleyball, according to the platform tennis association.

Topography and other obstacles, which the pair called “lucky incidents,” shaped the game. A rock was in the way, so the platform couldn’t be wider than 20 feet. The ground fell off sharply in another direction, restricting the platform’s length to 48 feet. The resulting area was too short for volleyball and, as it was unsheltered, unsuitable for badminton, Cogswell and Blanchard decided. So they started playing deck tennis with the rectangular paddles and spongy balls that Cogswell found in a sporting goods store.

Missed balls rolled down the hill, so Cogswell and Blanchard enclosed their court with chicken wire. That successfully corralled the balls, but it didn’t leave them enough room to swing their paddles.

“This led to the decision, which in the opinion of all present-day players, has ‘made the game,’” the association says. “They decided to allow players to take the ball off the back or side wiring: that is, as it bounced off the wire after having first hit inside the proper court, and before it had hit the platform a second time … If the landscape had allowed the court to be lengthened, it would never have been discovered how much this new rule added to the fun of the game.”

- Courtesy Of Errol Nattrass

- A platform tennis court at Burlington Tennis Club

And fun is the dominant strand in this game’s DNA. Once Cogswell and Blanchard built their court, friends and family gathered around to socialize and fine-tune the rules. They called themselves the Old Army Athletes, after Old Army Road, where Cogswell’s house was located.

They started a “marital championship” with 16 husband-and-wife teams. “There was a penalty of one point for each time a husband criticized the play of his wife, and vice versa,” association history says. “The judges had to listen carefully to detect any faint signs of sarcasm when sweet remarks seemed somewhat overdone.”

Platform tennis members used to skew older and male, Nattrass said, but women and younger people are increasingly playing the game. A seasonal platform membership at BTC starts at $420 — or $190 for first-time members under age 25. Some groups pay extra to reserve the same time slot each week.

A small warming hut with big windows sits between two of the courts. A grill just outside facilitates pre- and postgame socials. One group brought in bourbon sirloin tips, Elizabeth “Muff” Parsons-Reinhardt recalled. “They were grilling those up while we were playing. It was very unfair. We were all salivating!” Once or twice a year, Bill Allen shucks oysters for his Wednesday group.

Players hanging out become a de facto cheering squad. The men who play before Waite’s women’s group on Mondays sometimes linger in the hut. “If we have a really long point, they’re, like, banging on the windows, you know, hooting and hollering in there,” she said. “So it’s fun.”

Snow, too, boosts camaraderie. Players pitch in because there’s no staff to clear the courts, Waite said. “Everyone understands: If you want to play paddle, you’ve got to put your time in shoveling.”

Parsons-Reinhardt is ready. “I love November,” she said. “It’s my birthday month. And it’s Thanksgiving, which is my favorite holiday. And it’s the start of craft show season.” And, of course, it’s platform tennis season.

The retired University of Vermont physical education instructor has re-gripped her racket, ordered a case of balls and pulled her duffel bag out of her closet. Paddle is her favorite racket sport “hands down,” she said. “Thank God paddle season is here.”