“I don’t know whether to hug or punch you: you’re from Tate!” So declared Bobby Baker, 73, on opening her door to Linsey Young, curator of Tate Britain’s new show Women in Revolt! Art and Activism in the UK 1970-1990. Young interviewed scores of women in their 60s, 70s and 80s to unearth work made for and within the community, rather than for collectors or curators. Many, like Baker, felt excluded by mainstream institutions such as Tate. Young won their confidence, turned their urge to punch into a collaborative hug, and pulled into the Millbank gallery works that their creators never imagined being shown there. The effects are extremely mixed.

Baker’s is the wittiest, most dramatic and engaging discovery — irresistible as the cookies with which it is built. “An Edible Family in a Mobile Home” recreates a work installed in Baker’s prefab house in Stepney in 1976 for one week (by when all the art had been eaten).

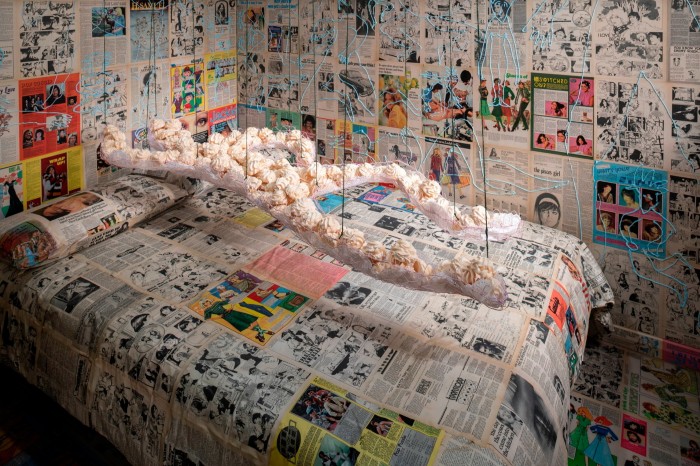

The teenage son, a skeletal Harlequin made from diamond-shaped Garibaldi biscuits, lounges in the bath. The meringue-fantasy daughter listens to music in a room plastered with Jackie magazine covers. Dad (fruitcake) slumps before the television. Baby (iced nappy) lies in a cot. Mum, pink dummy, breasts bursting with bounty, is refillable — ever giving, ever feeding.

Occupying Tate’s lawn like a benevolent sit-in, this hippy Hansel and Gretel house, where it’s a political act to gobble up the nuclear family, has an imaginative generosity and unpredictability largely missing from the rest of the show. For although Women in Revolt! is billed as “a major survey” of feminist art in the UK, it really isn’t. The show lacks the stellar artists emerging in the period — no Paula Rego, no Cornelia Parker. It is really about women’s activism: a duller, harder subject.

As social history, the show is informative. Sue Crockford’s film A Woman’s Place records the heady first Women’s Liberation Movement march in 1971. There’s extensive chronicling of Greenham Common protesters whose commitment blazes from photographs — white-haired “Grannies against Nuclear Winter”, veiled girls in “Brides against the Bomb” marrying then deflating a giant blow-up Trident missile.

Documentary photography, a medium where women excelled from the start, is well represented. Melanie Friend’s “Mothers’ Pride” is an engrossing study of teenage mums, desperate and defiant. Brenda Agard’s “Portrait of Black Women” sensitively unfolds resilience and diversity, counteracting racist assumptions. The wonderfully named Hackney Flashers’ photo-essay about nursery facilities, “Who’s Holding the Baby?” (1978), remains topical.

On the plus side too, the exhibition is viscerally evocative of the period’s casual everyday sexism, showing what women were challenging, and of the means with which they did — the 1970s homespun aesthetic of screen-prints, textiles, collage, graffiti. In “Spray It Loud”, Jill Posener displays gleefully defaced advertisements including Fiat’s “If it were a lady, it would get its bottom pinched” — the scrawled reply is: “If this lady was a car, she’d run you down”. In community workshop See Red’s poster “Protest”, a woman spews out Miss World stereotypes. Anyone remembering the 1970s will look back to such protests as almost nostalgically innocent.

But a little of this goes a long way, and Tate has mustered hundreds of works so minor, and often puerile or even hate-fuelled, that it’s extraordinary to encounter them in a museum: Poly Styrene’s condoms and cartoon collage “Germ-Free Adolescents”; Brenda Prince’s photographs of the banner “Angry, Manhating, Lesbian & Proud”; scores of trite objects — baby’s bottle with gift tag, gingerbread man inscribed “Men to Me Memento” — comprising Postal Art, items made and exchanged by women in 1975-76.

The misjudgment of parading ephemera as gallery-worthy exhibits is fatal — and a wasted opportunity. The 1970s were an astonishing moment for women’s art, when second-wave feminism — demands for equality, reproductive rights — met the beginnings of conceptualism. It could have been a fascinating subject.

Among the acknowledged pioneers was Helen Chadwick, kitted out in domestic appliances — cooker plate breasts, washing machine drum as belly — for “In the Kitchen”, and Linder Sterling, in concert at Manchester’s Hacienda wearing a dress made of meat products, slit to reveal a dangling sex toy. These legendary performances are commemorated here in photographs and videos, and the artists’ rigorous formal strategies and comic inventiveness, indebted to Dadaism and absurdist theatre, contrast glaringly with the majority of obscure, humdrum make-and-mend pieces which have no aesthetic distinction.

The same can be said for the handful of paintings, chosen for their narratives of oppression. Maureen Scott’s post-constructivist, dourly exasperated “Mother and Child at Breaking Point” opens the show and sets the mood. Houria Niati takes on Delacroix — the vanity! — in a quartet of seated women with caged heads, “No to Torture (After Delacroix, ‘Women of Algiers’)”. In Bhajan Hunjan’s formulaic “The Affair” a woman pushes at a wooden screen, “metaphor for . . . physical and mental enclosure”, according to Tate, which has just bought it.

Other Tate purchases from the show include Su Richardson’s “Bear it in Mind”, dungarees hung with crocheted sausages, scouring pads and claw-gloves, addressing “feminists’ concerns around . . . the often-unequal load of domestic responsibilities and child rearing on women”.

Aargh. In the introductory caption, “Rising with Fury”, Tate explains that the women here “made art about their experiences and their oppression”. The soundtrack rages in sympathy — punk musician Gina Birch’s “3 Minute Scream”, piercing yells from Robina Rose’s “Birth Rites”. It made me want to scream. At a time of much terrible oppression of women and children exposed in news reports from across the world — the ending of any rights at all including education in Afghanistan, the assaults of the morality police in Iran, the continuing atrocity of female genital mutilation in some African countries — this domestic bleating is tone-deaf.

But one work resonates, in quality and seriousness, above all else, and it is rooted in a British tragedy. Marlene Smith’s “Good Housekeeping III” is a larger than life multimedia relief/sculpture of a black figure with a mask-like Picasso face, clothed in white, holding fast to the wall alongside a happy family snapshot. Above, the caption reads “My mother opens the door at 7am. She is not bullet proof”. She is Cherry Groce, mistakenly shot and paralysed by police officers in an incident sparking the 1985 Brixton riots.

Although a reconstruction of a fragile lost work, this is what Tate should have bought, and displayed alongside Chris Ofili’s “No Woman No Cry”, depicting murdered teenager Stephen Lawrence’s mother Doreen.

This is an experimental show pushing to the brink what Tate has been increasingly attempting recently: to erode differences between activism and art. “If we break with the idea of the isolated artist in their studio,” writes Amy Tobin in the show’s catalogue, “and all the judgments around greatness, beauty, quality and apoliticism that follow from this, then what we determine to be artwork or who we consider an artist may change.” It has already happened, and the result is a politically driven, incoherent mess.

To April 7, then National Galleries of Scotland from May 25 and Manchester’s Whitworth in 2025, tate.org.uk