As an academic who studies social policy and race, I was not surprised to learn of the resignation of Claudine Gay, former president of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who was the first Black woman to have the role.

I was not shocked by the news that Antoinette Candia-Bailey, an administrator at Lincoln University of Missouri in Jefferson City, had died by suicide, amid concerns of harassment and a lack of support from senior colleagues.

Black female scholars and staff members continue to face exclusion and challenges in academia that often remain ignored.

A few years ago, I gave evidence to the Women and Equalities Committee of the UK Parliament at a session on racial harassment at British universities. I shared the example of a Black woman who had been driven out of her institution and treated so abysmally in the process that she had considered taking her life. To my knowledge, no one at that university has been held to account. I also outlined findings from my study of the career experiences of UK Black female professors who described being passed over for promotion in favour of less-qualified white faculty members, being undermined by white female colleagues who otherwise champion feminism, and having to take deliberate steps to protect their well-being (see go.nature.com/43bv84e).

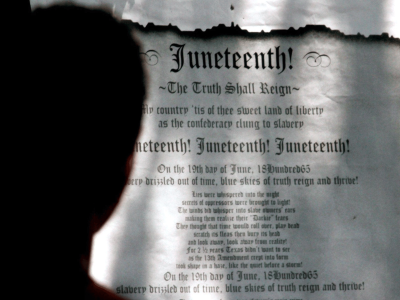

Why Juneteenth matters for science

I do not stand outside the issues I research. I have long been aware of the opaqueness with which institutions interpret and apply policies, and how this benefits certain groups but disadvantages others. I was so scarred by my previous experiences of applying for academic posts that, at one point, I took to walking around with the promotion criteria for senior lecturer at that university in my pocket to help me decide which work requests I should commit my time to.

I submitted my application to the university with confidence. It met the listed criteria for senior lecturer and many for the level above that. Yet my application did not pass even the first of three review panels. The amount of research funding I had secured was deemed not to be ‘sufficient’. There had been no mention of this in the guidelines. Introducing subjective language such as ‘sufficient’ risks inviting bias into the process.

The low representation of Black women in senior posts cannot be attributed merely to a pipeline issue. Resolving poor retention — by creating environments in which Black women can flourish — is crucial. This goes beyond ‘dignity at work’ statements, ‘diversity and inclusion’ policies and lunchtime yoga sessions. Black women are more likely than white women to die in childbirth (see go.nature.com/3pcukgs) and to have fibroids, and less likely to receive adequate pain treatment from health-care professionals. This means that Black women are often facing these challenges while also dealing with workplace difficulties, such as unsupportive line managers, isolation and the weight of academic service.

Existing at the intersection of being Black and a woman is exhausting.

Colleagues keen to demonstrate their solidarity with Black women might, at a minimum, commit to the below actions. Although these principles should be considered good practice, in general, not adopting them could have a disproportionately large effect on Black women, because of the existing challenges we face.

Equity is more than a buzzword

Be respectful of our time. I often receive requests — some even outside work hours — with unrealistic deadlines, without apology or explanation. When asking us to do something, acknowledge that we already have other commitments.

Pay us. Asking people to work for free implies that you do not value them or their expertise. If your business has a healthy bank balance or you are charging people huge sums to attend your conference, it is not reasonable to hide behind honorariums as a rationale for not paying contributors.

Sponsor Black women. In many ways, progress in academia — and in wider society — depends on who you know. While we continue to fight for recognition by and access to institutions, you can help us by citing our work and championing us.

Be transparent and honest in communications. If you can’t accommodate a request or commit to a project, say so. Avoid ambiguous language that requires us to read between the lines.

White women: feminism means Black women, too. In my study, Black professors described how white women excluded them through behaviours similar to those that the same women criticized in men. Working in solidarity with Black women means attending to the ways your racialized identity affords you privileges.

Unless such actions are integrated into workplace policies and practices, and unless people are held accountable, Black women will continue to be on the receiving end of disrespectful, exclusionary behaviours.

Black women must be vigilant about their health and well-being, and put firm boundaries in place to protect themselves. We must support and champion each other and be wary of narratives based on other people’s ideas of success, such as being called a role model, or “if you see it, you can be it”. Our challenge is not one of individual motivation, aspiration or achievement, but of the need for radical change that breaks down the barriers that, despite our efforts, continue to impede our collective success.