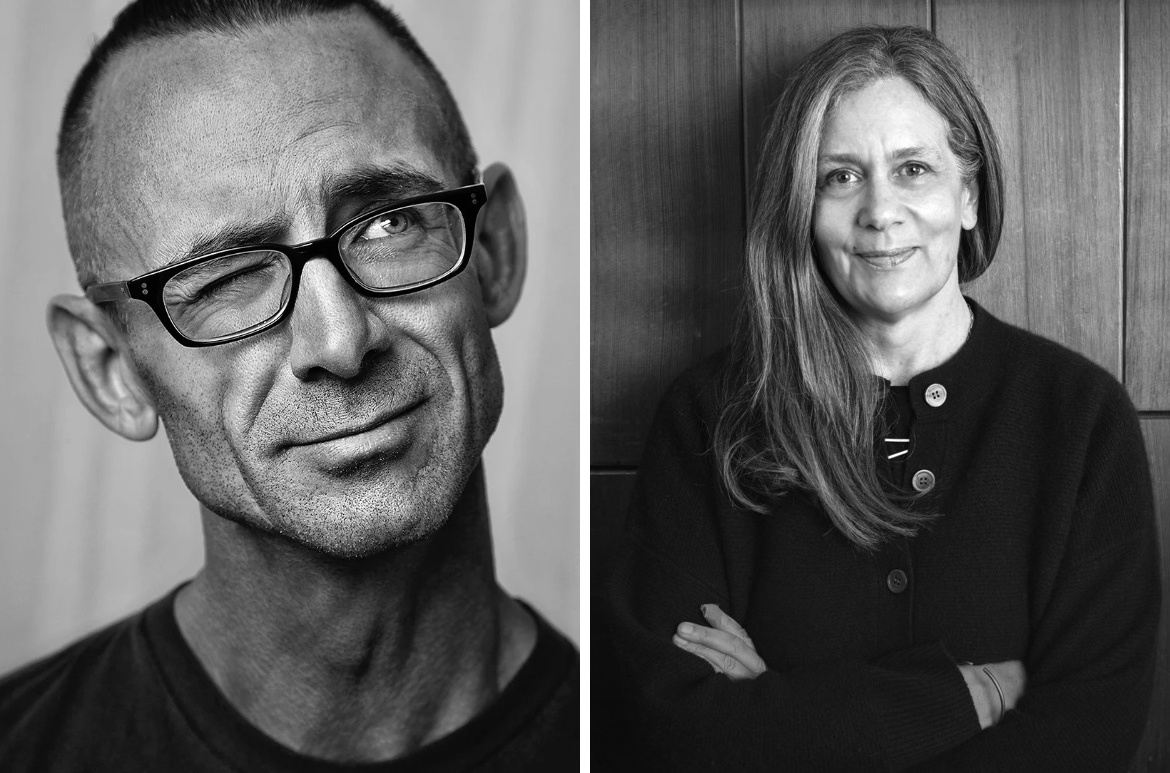

The web of literary influence is a tangled web indeed. We’re attempting to unravel it by talking with the great writers of today about the writers of yesterday who inspired them. This month—fittingly enough, considering our proximity to Halloween—we spoke with one literary horror writer and another who writes about literary monsters, both of whom discuss two very different authors whose work overlaps in surprising ways. Chuck Palahniuk (Invisible Monsters, Not Forever But for Now) talks about Ira Levin, best known for his domestic horror titles Rosemary’s Baby and The Stepford Wives. Claire Dederer (Monsters, Love and Trouble) explores the kitchen sink domestic analysis of Laurie Colwin, regarded for her novels and memoir-cum-cookbook Home Cooking.

Chuck Palahniuk on Ira Levin

Why Ira Levin?

He was such a jack of all trades. He started with television, and it was all about creating these very small dramas that had to escalate very quickly with very little resources in terms of money or characters or sets. He did Broadway shows—he did Deathtrap. He even wrote a song for Barbra Streisand that was a big hit. He was all over the map.

Another thing—he was always so good at plotting. My generation grew up with literature bad-mouthing plotting—that plotting was dead and artificial. People discarded the idea that a story could be well-plotted, but I thought it was just laziness. I think people just kind of gave up because they weren’t good at plotting.

I am so often disappointed by fiction. I like very, very little fiction—especially horror fiction—so when I find an author who can give me the story, give me a lot of different plot twists, and do it all with very limited characters and settings, and deliver a lot in very little pages even, I keep going back to their work. Stephen King has said that Ira Levin was a Swiss watchmaker of plot. Everything looks so gorgeous and simple and approachable, but on the other hand, it was so incredibly complicated and beautifully assembled.

He was great at pulling the rug out from under his characters.

Just very good plotting. Everyone kind of lives in their own…what they hope is reality. But then they find out that there’s always some sort of mechanism working behind the scenes. And typically in Ira Levin’s books, they find out too late what that thing is.

How do you think his TV work impacted his novels?

He was writing these dramatizations where everything had to be externalized. You couldn’t just have a character suddenly feel sadness or be overwhelmed by some abstract emotion. Everything had to be manifest through gestures and through physical acts. That training made him very good about doing that in the books themselves. This very simple scene setting in this very action-oriented series of events where everything was so tangibly demonstrated or put on the page. Emotion wasn’t dictated.

Across all Levin’s work, is there one thing in particular that sticks with you?

I’ve read and reread Rosemary’s Baby one hundred times and one thing that continually haunts me is the dream sequences. There are three dream sequences in Rosemary’s Baby, and each one of them seems to hint at a kind of predetermination. There are things in the dreams that Rosemary wouldn’t know yet that seem to act as a kind of microcosm of the plot that’s going to take place over the entire course of the book. Then at the end when Minnie Castevet says it was predestined, all these things have come to pass because you were predestined to bear the devil’s child, and the dream sequences seem to really underscore and prove that. I think that’s an aspect of the book that is never really appreciated until you have read it 10,000 times.

I’m always telling my students do not use dream sequences because people don’t really know how to do them, and most of my students just do them to imply emotional state. When Ira did them, he was telling the story on a meta level, and implying a whole different third or fourth layer of the story. Which is just another example of his brilliance.

Claire Dederer on Laurie Colwin

What drew you to Laurie Colwin’s work?

I have been a reader of Laurie Colwin since I was in high school in the 80s. That she could be so strongly voiced and so funny made me feel incredibly full of possibility in terms of my own secret and burning ambitions to be a writer.

I think the second thing that really made her important to me—especially when I was a young mother and I began writing books—was her emphasis on domesticity. The novels are intensely domestic, and she’s talked about how interested she is in how people live. And she has become even more famous for her food writing than for her novels and her short stories, but the food writing and the fiction share something, which is, it’s not a valorizing of domestic life, or saying domesticity is somehow positive or good. It’s just looking at domestic life, and it’s so deeply literary. For me, as a young memoirist, this idea of the importance of domesticity and the centering of domesticity as lived experience was a huge amount of permission. It made me realize this is something that I and a lot of other female writers are very interested in that can sometimes be shunted off or treated as unimportant because it has traditionally been a female experience.

In Happy All the Time she takes a traditional kitchen sink setup and then kind of plays with the gender roles in a nontraditional way.

There are ways Colwin can look a little bit hidebound. There’s a lot of money. There’s a lot of well-educated, genteel job-having. And there’s a lot of heterosexual romance between white people. But there’s something really interesting going on with the way the men and women interact. I think one of the reasons that she’s been so important is this reversal of these gender roles and this kind of inside-out quality where the men are sort of hapless yearners and the women are going about their lives.

I also think that one thing that’s a factor of her longevity is her refusal to moralize. One thing that her books really share is an almost gleeful and nonstop engagement in adultery. Most notably it’s dealt with in the novel Family Happiness. It’s not quite irony. She’s really thinking about what makes family happiness, and yet at the end of the book, she basically decides to keep having the affair. Colwin does not punish her heroines or make people suffer for falling outside the straight and narrow. That gives you an idea of how plot works with Laurie Colwin, which is to say not very much.

It’s an interesting way to explore a character. Rather than having them overcome major events, you simply see them exist.

There is a way that you picture her novels almost like a series of illuminated windows. My great-grandfather loved to play a game which he called simply, and a little disturbingly, “looking in people’s windows,” where he loved to walk around the neighborhood at around five or six p.m. when lights were on but before curtains were drawn and just see what he could see about how people lived. And I think that Laurie Colwin shares this intense interest. I think there’s a kind of genius in her allowing that to be sufficient.

I read an early review of Happy All the Time, and this reviewer really did not care for the book and talks about how it doesn’t tangle with its own themes—how should we live now—and it’s such a misreading of the book. I think Colwin’s job is to show how people live, and the sufficiency of just showing that—not moralizing, not overplotting, not sort of taking a theme out and trotting it around on a leash—I think there’s a real beauty, courage, and even a kind of genius to that. A reminder that there’s all kinds of people living all kinds of incredibly weird and fascinating ways around us, and that their humanity even exists is something we all struggle with on a daily level. The best writing shows us that.