The results from each stage of the MRC guidance resulting in development of the ‘Healthy Habits in Pregnancy and Beyond’ or ‘HHIPBe’ intervention are outlined below.

Identifying the evidence base

Need

Epidemiological evidence indicated an increased prevalence of overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age, with data from NI showing that more than one in two women enter pregnancy with excess weight [20]. By 2025, globally it is expected that 21% of women will have obesity and 9% will have a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 [52]. In the UK, around 50% of pregnant women have overweight or obesity at the start of pregnancy with approximately 5% having a BMI over 35 kg/m2, a risk factor for maternal morbidity and mortality [53, 54]. However, entering pregnancy with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (excess weight) is also associated with a number of health risks for the mother and baby based on systematic review evidence [55,56,57,58]. Furthermore, maternal obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) can increase the risk of developing a range of health complications throughout pregnancy for both the mother and the fetus including, gestational diabetes mellitus, gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsis, venous thromboembolism, labour complications, caesarian section, depression and premature birth [59]. Such evidence highlights the need to provide evidence-based services to support this pregnant population (BMI > 25 kg/m2) with health-promoting behaviours that may aid behavioural management of GWG and minimise risks. Yet, despite this, there is a lack of support available in NI and ROI regarding healthy eating and physical activity behaviours in pregnancy. Specifically, intervention approaches are needed that are evidence-based, theoretically strong and scalable, with regard to implementation in the current healthcare systems [24].

Evidence reviews on obesity and pregnancy point to the need for person-centred care, particularly for women with higher BMIs who regularly report negative experiences during antenatal care based on their weight [60]. This stigmatisation of women due to body shape or size was found to be highly prevalent across the reproductive stages (i.e., preconception, pregnancy and postpartum) in one review [61]. Therefore, despite pregnancy being considered a ‘window of opportunity’ because it is a time when women are in frequent contact with healthcare professionals and may be more receptive to health improvement messages, care is required to ensure interventions are supportive, and non-stigmatising [61,62,63]. Indeed, women with obesity have expressed a desire for additional behavioural support during their pregnancy yet, simultaneously, reported feeling stigmatised by healthcare professionals because of their weight, leading to a reluctance or hesitation in seeking support or advice on health or weight during pregnancy [64,65,66]. One way to ensure that any intervention is appropriately designed to meet the needs of the target population is to embed PPI within its development in order to ensure it is appropriate, sensitively and respectfully framed (described fully under Results: Modelling process and outcomes below).

Identify and develop appropriate theory

Habit theory

Healthy diet and activity ‘habits’, i.e. habitual behaviours, are the goal of most weight-management programmes, but few draw explicitly on habit-formation theory. The essential feature of habits, once acquired, is that they are ‘automatic’ (i.e. require minimal willpower or deliberate effort) [67]. Research shows that repetition of a behaviour in a consistent context enables it to acquire automaticity, and once automaticity is established, it is more resistant to extinction than deliberative (intentional) behaviours [68, 69]. Habits are defined as ‘psychological dispositions to repeat past behaviour’ [70] and habit indicates “a process whereby exposure to a cue automatically triggers a non-conscious impulse to act due to the activation of a learned association between the cue and the action” [25, 71]. The main components of habit-formation include behavioural repetition, associated context cues and rewards [72]. According to Gardner et al., habit-formation involves three phases; the ‘initiation’ phase, ‘learning’ phase and the ‘stability’ phase [24, 67]. The ‘initiation’ phase involves planning what the intended behaviour is and which context/cue will be used to do the behaviour, the ‘learning’ phase involves repeating the behaviour in the selected context/cue consistently and, finally, the ‘stability’ phase is when the habit has been formed and the behaviour is automatic or ‘second nature’ to the person [24]. The habits formed may be more resistant to lapses and, therefore, are expected to be maintained over the long-term [23, 71,72,73].

The first habit-based behavioural intervention promoting a set of negative energy-balance behaviours via a leaflet, alongside advice on repetition, context-stability and self-monitoring showed significantly greater weight loss in the habit group compared to the control condition (habit group: -2.0 kg; control: -0.4 kg) at 8 weeks follow-up; and, unusually, for behavioural treatments, modest weight loss continued after the end of the active treatment period, up to 32 weeks [27]. Weight loss was associated with increased ‘automaticity’ of behaviours, suggesting that habit-formation underpinned the effectiveness of the intervention [27]. These findings were confirmed in a definitive RCT in adults with obesity drawn from primary care (‘Ten Top Tips’ [10TT] RCT), where 10TT was explained by healthcare staff (approx. 25 minutes), with no further clinical contact [26]. The 10TT group lost significantly more weight over a three month intervention period compared to those receiving ‘usual care’ and, at 24 months, the 10TT group maintained their weight loss and showed significant gains in automaticity; making this an effective, low intensity and low-cost treatment option (£23 per participant) [26, 28].

Habit-formation theory is a relatively novel theory to underpin lifestyle interventions for weight management [23, 71, 72]. It has been used successfully in weight management interventions for various population groups [21], but has not been tested via behavioural intervention in a pregnant population. Alongside this focus on the theoretical basis for the behavioural intervention, existing evidence regarding the BCTs associated with intervention effectiveness in previous GWG studies was examined, given additional BCTs are likely to aid enactment of new, planned, healthy behaviours in the initial stages of habit-formation [36, 37, 39].

BCTs

A rapid review was conducted during the intervention adaptation to explore the components of successful GWG interventions. Of the 22 interventions that reported BCT content, the most commonly used BCTs were goal setting, self-monitoring, feedback on behaviour and barrier identification/problem-solving. Habit-formation has also been identified as an important BCT in weight management interventions [21]. Although “habit-formation” is described as a BCT in the BCT Taxonomy (v1): 93 hierarchically-clustered techniques, there are additional BCTs which may support the movement through the different phases of habit-formation [36, 71]. Gardner and Rebar (2019) examined the BCTs which were commonly used to promote habit-formation in previous habit-based interventions and found the following BCTs were used most frequently: “habit-formation”, “use prompts and cues, “action planning”, “provide instruction on how to perform the behaviour”, “set behavioural goals” and “self-monitor behaviour” [36, 71]. Aside from reporting frequency of use, there was limited research linking BCT usage with effectiveness of the interventions. Two systematic reviews examined the most effective BCTs used in weight management in pregnancy interventions [37, 74]. Soltani et al. (2016) found the following BCT categories to be the most commonly used in interventions that were successful at limiting GWG; “feedback and monitoring”, “shaping knowledge”, “goals and planning”, “repetition and substitution”, “antecedents” and “comparison of behaviours” [37]. For interventions which focused on diet or diet and physical activity, the most successful BCT categories were “feedback and monitoring”, “shaping knowledge”, and “goals and planning” [37]. This is important as planning and self-monitoring are key elements of habit-formation theory [23]. In addition, an earlier systematic review by Hill et al. (2013) which used the CALO-RE taxonomy to code the BCTs embedded in pregnancy weight management interventions, found “providing information on the consequences of behaviour to the individual”, “provide rewards contingent on successful behaviour”, “prompt self-monitoring of behaviour” and “motivational interviewing” were the most effective BCTs used to help limit excessive GWG [40, 74]. Another systematic review which focused on exclusively digital health interventions in pregnancy, found that interventions which included a greater number of BCTs (particularly involving goal setting and self-monitoring) were more effective than others [75].

Of the original 10TT BCTs coded by Kliemann et al., all were retained in the adapted intervention (HHIPBe) aside from ‘goal setting (outcome)’ and ‘‘prompt review of outcome goals’ (see Table 1 for full details on BCTs in 10TT and HHIPBe) [39]. This was because the HHIPBe intervention focuses on turning the ten tips into habitual behaviours, rather than focusing on weight as an outcome goal, therefore women were only encouraged to set goals in relation to their behaviour. The ‘prompt self-monitoring of behavioural outcome’ BCT was retained as participants were given the option to record their weight throughout their pregnancy, if they wished. BCTs were integrated throughout the intervention materials, for example, “teach to use prompts/cues” was incorporated in the HHIPBe leaflet – “Add reminders to your environment and be prepared to carry out your habit (e.g. place this leaflet in a prominent position and have fruit available each day at breakfast).”

Modelling process and outcomes

This section details how the 10TT intervention content was adapted for pregnancy and illustrates the role of PPI collaborators from the target population in shaping intervention design and content.

PPI Results/Outcomes (GRIPP2 SF Heading) – Women who came forward via the posters tended to either not have experience of living at a higher weight (i.e. a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) during a recent pregnancy, or wanted to take part in the research rather than collaborate in developing the intervention. Seven PPI collaborators were recruited from letters sent to previous research participants, two were recruited via word of mouth and one via the posters. Of these, ten initially engaged, and six became actively involved as PPI collaborators throughout. The PPI collaborators chose the name for the study – ‘Healthy Habits in Pregnancy and Beyond’ or ‘HHIPBe’. PPI collaborators also significantly influenced the content and design of the HHIPBe intervention materials.

Development of the HHIPBe participant leaflet

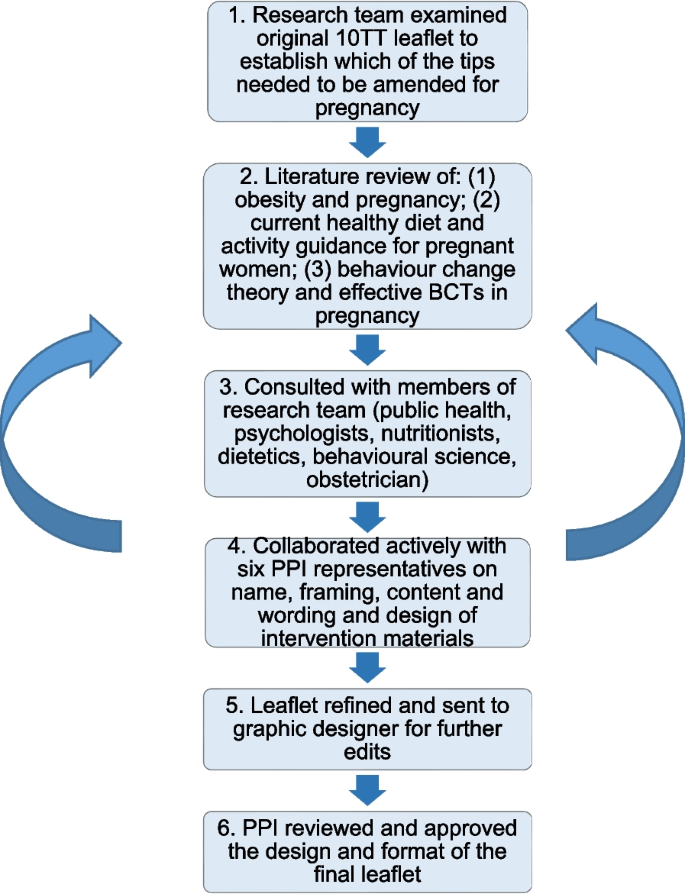

Participant materials: Figure 1 outlines the process of adapting the original 10TT intervention leaflet using an iterative process of review and amendment by the research team (MMcK, LMcG, DG, CMcG and JMcC) and PPI collaborators.

Summary of the development of the adapted HHIPBe participant leaflet

Following initial review of the original 10TT leaflet by the study team a draft adaptation of the leaflet was initially created by the research team. The adapted leaflet provided a scientific rationale for each of the top tips modified in line with pregnancy-specific available guidance (see Table 2 for two examples (out of ten)).

The main consideration when adapting the 10TT leaflet was to remove the focus on weight loss, as this is not appropriate for a pregnancy intervention [78]. Many of the ‘handy hints’ for the tips included calorie information which was removed. Practical examples in the tips were revised to be specific for pregnancy, for example, the original leaflet suggested standing on a bus while travelling for the “up on your feet” tip, however, this would not be advisable for pregnant women for safety reasons. The leaflet was also modified to include relevant food safety advice such as guidance on caffeine intake during pregnancy.

Figure 2 presents an example page from the final version of the leaflet which was designed and printed by a graphic design company. The PPI collaborators were generally positive about the first draft of the participant leaflet; they found it was clear and concise with a good balance of encouragement and information. PPI collaborators created the frequently asked questions section of the leaflet and helped identify pregnancy specific challenges such as cravings, nausea and heartburn, with examples added on how to deal with these.

Example page from the adapted HHIPBe participant leaflet

PPI collaborators also provided guidance on the terminology to describe weight throughout the intervention for example, using person-first language such as “having excess weight” rather than “being obese”. PPI collaborators suggested making the language more welcoming and empathetic, particularly in the introduction section of the leaflet, and wanted more practical suggestions to help facilitate the 10 tips becoming ‘habitual’. They also suggested including more examples for pregnant women who are working/in employment, as well as for women who do not work and, whilst they liked the design and use of images in the leaflet, they recommended a change of font colour to improve readability. The final leaflet consisted of 12 pages and included introductory text and information on why it is important to manage weight during pregnancy, ten tips with a description of each of the tips and some ‘handy hints’ on how to achieve the tips, a frequently asked questions section, a shopping guide, links to further information and an example tick sheet. The leaflet encourages participants to use the logbook or app to log their progress with the tips.

Development of the HHIPBe Participant Logbook

Similar to the leaflet, the HHIPBe logbook was adapted from the original 10TT logbook and reviewed/redesigned by members of the research team and PPI collaborators. The original 10TT intervention included a logbook for participants to monitor their daily progress with the ten tips and provided a space to plan how they would achieve each of the tips. The final logbook was designed and printed by a graphic design company in the same style as the HHIPBe leaflet.

In line with the leaflet, PPI collaborators modifications to the HHIPBe logbook included ensuring empathetic and friendly language was used, such as, “we hope you find it useful to use alongside the HHIPBe leaflet” and “developing habits may require some effort at first, but if you follow the tips every day, and do them in the same place or at the same time, they will become automatic and easier to stick to”.

An additional column was added to the notes and planning sheets, entitled “my tip”, which allowed participants to make the tip specific to them and set specific goals in relation to the tip. Alternative examples were incorporated to ensure they were suitable for pregnancy and an additional section was added to the tick sheets to allow participants to reflect on the past week, and make any notes on the tips that they were struggling with. Figures 3 and 4 show examples of the notes and planning sheet and tick sheet from the HHIPBe participant logbook.

Example notes and planning sheet from the HHIPBe participant logbook

Example tick sheet from the HHIPBe participant logbook

The ‘record your weight’ section was also amended; in the original 10TT logbook, participants were encouraged to record their weight daily and it was included in the tick sheets. For the HHIPBe logbook, this section was repositioned to the back of the logbook and was optional for women. Women were encouraged to record their weight no more frequently than weekly and to speak to a healthcare professional if they noticed any weight loss or had any concerns about their weight. One PPI collaborator suggested expanding the explanation on the ‘recording your weight’ section and why it was needed, which was subsequently added into the logbook. Information on adequate GWG according to the IOM guidelines was also added to the leaflet [3].

PPI collaborators found the example notes, planning sheet and tick sheet helpful and liked that the example sheet was ‘realistic’, as it showed that someone did not achieve all of the tips. They liked the format of the logbook, however, wanted a larger space to write in goals and notes. The size of the logbook was changed from A5 to A4 based on PPI feedback to ensure there was enough space for the participants to make written notes and set goals in the logbook. All PPI collaborators comments were incorporated before the final logbook was printed.

Development of the HHIPBe participant (mobile) app

The app aimed to be user-friendly, have the same functionality as the logbook and offer an alternative to using the hard copy (A4) logbook and/or leaflet, given apps offer a convenient ‘anyplace, anytime’ way of accessing advice or monitoring tools [91,92,93]. All of the information included in the leaflet is included in the app but it also allows participants to log their progress with the tips. Participants can choose to use the app instead of the logbook.

The research team reviewed the list of essential features on the 10TT app, and modified it in-line with the HHIPBe versions of the leaflet and logbook [94]. Three PPI collaborators tested the HHIPBe app, helping to resolve initial issues with registering and logging onto the app. PPI collaborators felt the app would be useful, liked the app functionality and layout and suggested minor wording and layout edits. A tutorial was co-created with instructions on how to use the app based on input from PPI collaborators.

The app contained a small number of additional features compared with the paper logbook. Firstly, it had a graphical function to allow the participants to observe their weight gain (in Kg or stones and pounds) trajectory throughout pregnancy, the weight tracking function could be turned off. Secondly, the original 10TT app sent daily notifications to the participants, which resulted in mixed feedback with some participants finding the frequency ‘annoying’ [94]. Therefore, weekly email notifications were scheduled for HHIPBe participants (who registered an account with the app) to encourage the women to track their progress and encourage engagement. The weekly notification sent to the participants read:

“Have you recorded your progress towards achieving the Ten Top Tips? You can do this by logging into the Healthy Habits in Pregnancy and Beyond app. Keeping a note of your progress will increase your success in developing healthy habits. Don’t worry if you forgot to log anything last week, it’s easy to add to past days. Why don’t you start now?”.

These additional features expanded the BCTs included in the logbook with regard to increased feedback on behaviour and additional prompting to monitor behaviour or outcomes of behaviour, as summarised in Table 1.

Healthcare professional training to deliver the HHIPBe brief 1:1 conversation

The overall HHIPBe intervention consisted of a one-off, brief (15–20 min) 1:1 conversation with a trained professional at the outset. During this 1:1 session, the trained professional explains the process of habit formation, encourages the woman to consider what habits they might focus on initially and goes through the leaflet, logbook and app with them. Women continue with their routine antenatal appointments as usual and are encouraged to get in touch with the antenatal care team if they have any questions or concerns at any time. The original 10TT intervention was delivered by a trained nurse or healthcare assistant during a dedicated face-to-face 20–25 min (approx.) session in a primary care setting [26]. Based on discussions with midwives in the early stages of intervention adaptation, it was desirable to reduce the length of the 1:1 conversation to take account of service pressures and increase the likelihood that the intervention could be incorporated into routine antenatal care delivery.

Previous research has found that midwives find it difficult to discuss weight with women [95]; a perceived lack of adequate and available resources, equipment and training to address the psychological and physiological needs of mothers with a high BMI [96] and concerns over how to communicate about the issue without impacting the patient/caregiver relationship and ‘normalise’ obesity are prevalent [95]. This aligns with the views of women with a high BMI, who also report a fine balance between healthcare practitioners outlining the risks and management of obesity in pregnancy, and the psychological and potential stigmatising impact of this [97]. Guidelines have been developed around the use of language to address weight in pregnancy [95,96,97] in order to avoid stigmatisation of individuals [45]. These guidelines highlight the 5 As framework (ask, assess, advise, agree, assist) to guide conversations between healthcare practitioners and patients and facilitate the discussion of GWG in a non-judgemental manner. Recent evidence illustrates this tool can be effective at initiating these types of conversations with patients [45, 98, 99] and so it was selected to form the basis of the HHIPBe training.

The content of several E-learning programmes that were already accessible to midwives was considered when defining the content of the training. These included resources developed by the Canadian Obesity Network on the 5As framework for obesity weight management [99] and the modified 5As framework for healthy pregnancy weight gain [45]. We also reviewed the ‘Making every contact count’ training [47] available to healthcare professionals in ROI and a similar E-learning tool developed by the Public Health Agency NI [100], both of which were designed to help healthcare professionals undertake brief interventions to promote healthy behavioural change.

Overall, the healthcare professional training covered: background information on why managing weight during pregnancy is important; the principles of habit-formation; the intervention materials and how to introduce them to participants; and, how to set SMART (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Timely) goals to aid the establishment of new health-promoting behaviours. The training included a section on how to discuss weight sensitively with women. It included role-plays for different scenarios the intervention facilitator might face when delivering the intervention and demonstrated key aspects of delivery including: asking an open question; showing empathy; active listening and reflecting when discussing the patient’s previous weight management experiences; problem solving; discussing motivation for behaviour change; talking through a few HHIPBe tips; and setting a goal. A checklist for the 1:1 conversation facilitator and notecards to guide the key elements of the conversation were developed to support fidelity of delivery. The brief 1:1 conversation reinforced the BCTs in the participant intervention materials (leaflet, logbook, app) and provided additional BCTs, for example, engaging in effective goal-setting, problem solving (encouraging the participant to think of potential barriers and enablers to repeating the chosen behaviour in a consistent context to facilitate habit-formation), and action planning.

The E-learning package took 1–2 h to complete and could be completed over multiple sessions. Intermittent questions to test understanding of the content were developed by the trial team and included in the resource. A certificate was provided at the end.

A logic model provided an overview of how the HHIPBe intervention was intended to facilitate positive health behaviour change (diet and physical activity) in pregnant women with overweight and/or obesity (Fig. 5).

HHIPBe Logic Model