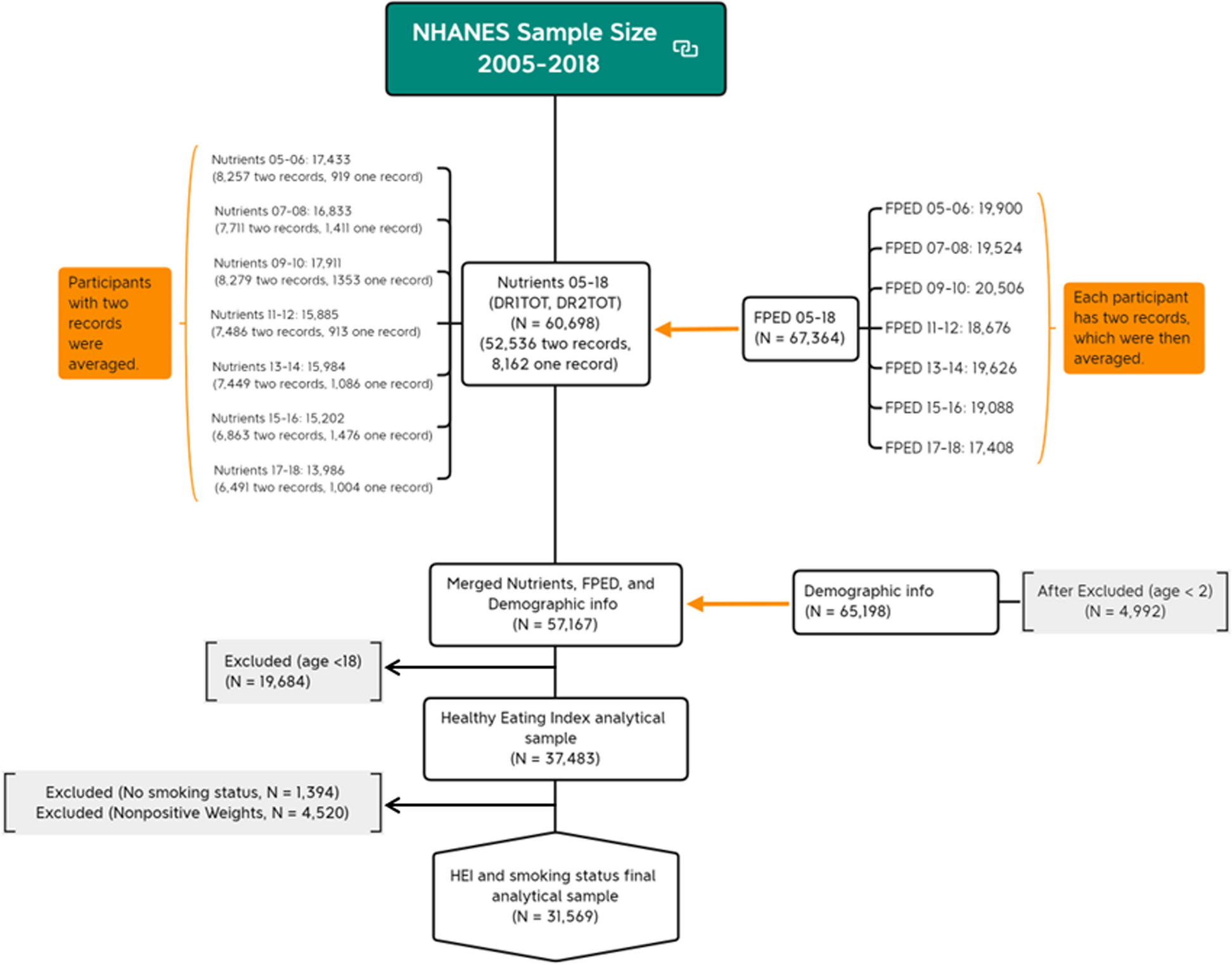

We utilized the nationally representative NHANES datasets from 2005 to 2018 to confirm our hypothesis regarding the association between dietary quality assessed by HEI scores and its 13 components among smoking status, categorizing individuals as current, former, and never smokers. Additionally, this study delved into the impact of smoking cessation duration on dietary habits, providing insights into the link between dietary quality and smoking status.

Our analysis found that 19.4% of adults aged ≥ 18 were current smokers, with a higher prevalence in men (22.5%) compared to women (17.5%). Between 2005 and 2019, cigarette smoking rates ranged from 20.9 to 14.0%, with men ranging from 23.9 to 15.3% and women from 18.1 to 12.7%, and our results fall in this range [36,37,38,39]. Current smokers were more prevalent among men, those with lower education, lower income, non-cohabiting individuals, and those without private insurance, consistent with previous CDC findings [36,37,38,39]. Our data also showed that smokers scored 4.78-point lower on the HEI total score than former smokers in adjusted model, affirming previous research [18]. The consistency with previous studies indicates the reliability of our analysis.

Our study also showed that former and never smokers typically had a better diet quality than current smokers, in line with previous research [13,14,15, 17, 18, 40, 41]. On the one hand, current smokers in our study reported consuming a higher amount of energy and carbohydrates (a primary source of energy) but less protein than former smokers. This pattern suggests a preference for energy-dense foods, which are often high in carbohydrates and fats but lower in protein. While no significant difference in saturated fat intake was noted between former and current smokers, the former group reported higher consumption of total polyunsaturated fatty acids (a healthier fat type).

On the other hand, current smokers were found to consume fewer fruits, vegetables, greens and beans, whole grains, and varied proteins, while having a higher intake of added sugars. Previous studies have reported that smokers tended to consume less vitamin C-rich fruits and vegetables, although they require more vitamin C to counteract the free radicals from smoking [18, 20, 40, 42,43,44]. On average, one cigarettes destroys about 20 mg of vitamin C [42], which has also been associated with lower serum vitamin C levels in smokers [41]. Moreover, our supplementary analysis of data spanning from the 2007–2008 to the 2017–2018 cycles revealed that current smokers exhibited lower vitamin C supplement intake (228.6 mg) compared to former smokers (244.7 mg) and never smokers (224.2 mg) (as displayed in supplementary Table 1). Furthermore, it is worth noting that vitamin E’s antioxidant function is compromised in the absence of vitamin C [43]. Considering the increased risk of chronic diseases resulting from the combination of smoking and poor dietary quality, with approximately 30 million current smokers in the US [36,37,38,39], it is important to continue raising awareness about the intake of fruits and vegetables for smokers. Further research is necessary to better understand and address the dietary challenges faced by smokers.

Moreover, our study revealed an unexpected finding regarding sodium intake, challenging previous research suggesting that smoking might influence taste perception and lead to a preference for saltier foods, implying higher sodium intake among current smokers [19, 20]. Instead, our findings indicated that current smokers reported lower sodium intake compared to former or never smokers. Actually, our supplementary analysis showed that the percentage of current smokers following a low-salt diet was not higher than former and never smokers (1.6% vs. 2.4% vs. 1.5%, respectively). We also found that a higher percentage of current smokers (40.6%) often used salt during cooking than former (34.5%) and never smokers (37.1%). Similarly, more current and former smokers used table salt recently (36.0% and 37.0%) than never smokers (29.2%). These additional findings support the idea that current smokers do not necessarily prefer less salt diets, in line with previous research [19, 20]. The reduced sodium intake observed in current smokers might result from their lower overall food consumption. The appetite-suppressing by nicotine effect may lead smokers to consume fewer meals than others [41]. Our study echoed this, as current smokers consumed fewer food items. While they had a statistically significantly higher energy intake in the unadjusted model, their diets were characterized by lower protein, higher carbohydrates (with higher sugar), and less fiber, suggesting a preference for high-energy-density or empty-calorie foods, which may contribute to their lower sodium intake.

Similarly, our study found no significant difference in saturated fat intake across current, former, and never smokers, deviating from prior research linking smoking to higher saturated fat consumption [15]. This variation might stem from the overall lower food intake reported by current smokers, aligning with previous studies suggesting that smokers generally consume less food [15, 41]. Consequently, this reduced consumption could naturally lead to lower saturated fat intake. Supplementary Table 2 in our additional analysis corroborates this: current smokers tended to have a less varied diet compared to former and never smokers (13.8 vs. 15.4 vs. 15.1, p < 0.001). Prior meta-analysis indicated that dietary variety significantly influenced food intake [45]. This can be particularly relevant when considering that smoking may impair taste bud function, potentially diminishing the appeal of food and resulting in decreased consumption.

Another significant finding was that light current smokers reported higher HEI total score than heavy smokers, and quitting smoking improves dietary quality than smoking, evident within the first year. This improvement could be due to restored taste perception, leading to healthier food choices for former smokers [46]. Moreover, former smokers who have abstained for 5–10 years had dietary scores similar to never smokers suggests that former smokers’ dietary behaviors tend to normalize over time. Quitting smoking not only improves lung health and reduces cancer risk as previous studies reported but also leads to better dietary choices [1,2,3,4].

However, current smokers are often concerned about weight gain after quitting, which can decrease their motivation to quit. It is worth noting that while former smokers, reported a higher obesity rate than both never smokers and current smokers (40.2% vs. 37.0% vs. 33.4%, respectively), a closer examination by quitting duration revealed a more nuanced picture. Specifically, among former smokers categorized by quitting duration (0–1 year, < 1–5 years, < 5–10 years, < 10–20 years, and 30 + years), the obesity rates were 38.7%, 42.3%, 37.1%, 43.3%, 42.7%, and 37.5%, respectively (see Supplementary Table 1). These findings indicate that the obesity rate does not significantly rise in the first year after quitting but increases between 1 and 5 years, and those who quit for 30 years have obesity rates similar to never smokers. It is also worth noting that the energy intake remained relatively consistent across different quitting durations; however, a decline in moderate-to-intense physical activity over time was noted, which could contribute to weight gain (see Supplementary Table 1). Thus, increasing physical activity and controlling energy intake may help for weight management. Previous research supports that regular weight monitoring and adjustments in diet and exercise are beneficial [26, 27]. Therefore, while quitting smoking might lead to initial weight gain, it can be managed with lifestyle adjustments.

Limitations and strengths

The present study exhibits several limitations. Firstly, its cross-sectional design prevents the establishment of causal relationships between HEI and smoking status. Secondly, the reliance on self-reported dietary intake data introduces the potential for recall bias and measurement errors, which could impact the accuracy of the results. Similarly, self-reported smoking behavior may also be susceptible to recall bias. Furthermore, the HEI calculation method adapted in this study is simple HEI scoring algorithm – per person. While this approach may not yield the most precise estimates of means with least biased as it does not account for the relationship between HEI components, it aligns with the objective of this study of gaining a broad understanding of the dietary habits within a specific population [35, 47]. This simplified HEI scoring algorithm per person effectively serves the purposes of our research.

Despite these limitations, the study has some strengths that enhance our understanding of dietary habits among individuals who are current, former, and never smokers. The utilization of a nationally representative dataset like NHANES bolsters the study with a robust sample size, thereby enhancing the external validity of the findings. Moreover, NHANES covers a wide spectrum of areas, enabling us to account for various factors that influence these associations, including sociodemographic factors, behavioral and lifestyle choices, psychological aspects, and chronic health conditions, thereby reinforcing the robustness of our analysis. Furthermore, the focus of this study on different current and former smoker subgroups holds potential value for public health practitioners and policymakers in formulating effective strategies for tobacco cessation initiatives.