In a concerted effort to integrate the health and sustainability agendas for food system transformation, the EAT Lancet Commission published the planetary health diet (PHD) in 2019, establishing the first scientific targets for a dietary pattern to promote both healthy diets and sustainable food production on a global scale by 2050 [1]. Meeting the PHD targets in most industrialized countries will require stark increases in the consumption of fruits, vegetables, nuts, wholegrain cereals, and unsaturated fatty acids, as well as decreases in the consumption of meat, dairy products, saturated fatty acids, and sugars [1].

To achieve such shifts, governments have at their disposal several behavior change interventions to promote population-level behavior change. One framework that is commonly used to taxonomize these interventions is the Nuffield Ladder of Intervention, which introduces individual freedom to choose as a key guiding concept [2]. Namely, the ladder distinguishes between ‘soft’ interventions (I.e., those on the lower rungs of the ladder), such as information and education, which infringe the least on individual choice and ‘hard’ interventions (I.e., those on the top rungs of the ladder), such as mandatory standards or bans, which intrude most heavily on individual choice. Following the foundational liberal values underpinning the ladder, the general principle for policymakers to follow is that, when possible and effective, soft measures are to be preferred over hard ones.

In the arena of policymaking for shifting food choices for health and sustainability reasons, most governments to date have favored the use of soft interventions [3]; however, these interventions have often been found to be either (a) ineffective at promoting long-term behavior change, particularly compared to interventions higher on the ladder; or (b) effective at promoting behavior change amongst those who are already better positioned in society to achieve the desired behavior change, thereby generating inequities along socioeconomic lines [4, 5]. One of the key reasons that has been posited for persistent reliance on soft interventions, despite evidence of low effectiveness, is the issue of acceptance: acceptance of hard interventions, which impinge more heavily on individual freedom of choice, may be low amongst several relevant stakeholders [4]. A systematic review of studies on public acceptance of policies to shift health-related behaviors offers support for this rationale, finding low public acceptance of interventions higher on the Nuffield Ladder relative to those interventions lower on the ladder [6, 7]. Low public acceptance is also inextricably linked to low policymaker acceptance, particularly in democratic contexts in which policymakers must navigate acting in the public interest while maintaining public favor for re-election.

It is in the context of this effectiveness-acceptance trade-off where the appeal of Thaler’s and Sunstein’s nudge can be easily understood. Thaler and Sunstein essentially posit that it is possible for governments and implementing institutions to effectively change behavior while maintaining individual freedom of choice. Such a balance may be achieved by use of a nudge, which refers to a shift in the way choices are presented to decision-makers (I.e., the choice architecture) that predictably alters behavior in the population without barring any options or significantly changing economic incentives [8]. In little over a decade since its first inception, nudging has already become a prominent consideration in the policymaking toolbox, as many governments and international development agencies have integrated ‘nudge units’ to guide policy and operational decision-making [9].

Growing evidence points to one particularly effective nudging strategy: the default nudge [10]. Default nudges, which have been highlighted for their potential to promote healthy and sustainable food choices across several studies [11,12,13], refer to a particular type of nudge in which the ‘default’ option – i.e., the outcome that arises when a decision-maker does not make an active choice – is altered by a choice architect to promote a shift in behavior.

While default nudges are a very promising tool from an effectiveness standpoint, questions of acceptance remain. Namely, while default nudges have been found to be relatively more acceptable to the public than more traditionally paternalistic tools that aim to restrict or eliminate choice [14], default nudges have also been found to be the least acceptable to the public amongst nudging strategies [15, 16].

Public acceptance has been raised as a key consideration in designing ethical nudges, as it serves as a proxy to understanding the extent to which each nudge aligns with the preferences of the population impacted by the nudge and thus the extent to which each nudge is legitimate [17, 18]. Indeed, while nudging first emerged with a promise to find the ethical ‘sweet spot’ in shifting behavior without infringing on individual freedom to choose, several objections have been raised by critics on the extent to which nudges really do so, particularly if they prey upon cognitive biases and heuristics in such a way that individuals end up choosing options that run counter to their actual preferences [17].

It is also of fundamental importance to understand the mechanisms underpinning public acceptance, or lack thereof. This importance draws from communication research, particularly the theory and empirical evidence for the effect of framing, defined as ‘the process by which a communication source constructs and defines a social or political issue for its audience’ [19]. Namely, the specific conceptualizations that are used to frame policies have been found to exert an, albeit moderate, influence on public attitudes towards those policies across several policy arenas, including those related to promoting healthy and sustainable food choices [20, 21]. Thus, understanding the factors associated with acceptance offers insights for levers that can be acted upon in the communication of a nudge to increase public acceptance.

Given the salience of public acceptance in designing successful nudges that carefully navigate the effectiveness-acceptance trade-off, this study aims to investigate public acceptance of a series of nudges designed to promote healthy and sustainable food choices amongst consumers in Germany. Germany makes for an applicable study context, as Germany has been highlighted as a pioneering country in the application of behavioral insights, with a ‘nudge unit’ based within the Federal Chancellery since 2015 [22]. In addition, public acceptance of health nudges in general has been found to be quite high in Germany [23], a context with limited adoption of more traditionally paternalistic nutrition policy instruments despite a persistently high burden of diet-related disease [24, 25]. This study is guided by two research questions, each expanded upon below.

Q1. What design changes improve public acceptance of default nudges for promoting healthy and sustainable food choices?

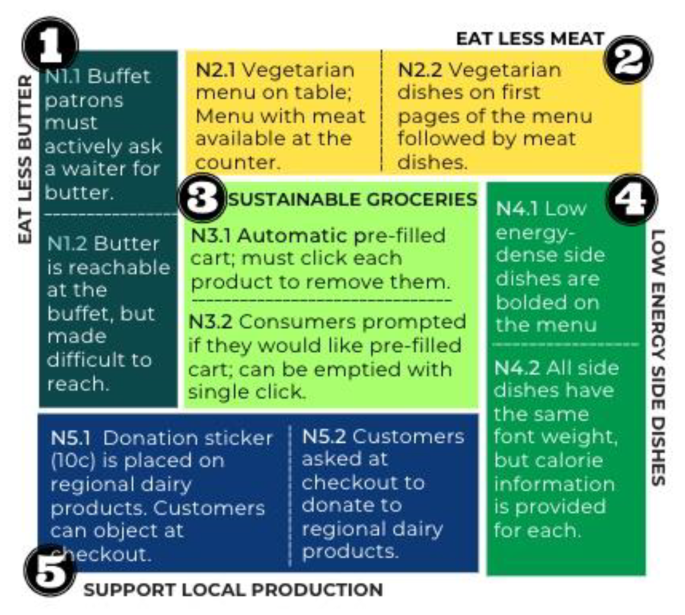

Given the understanding that nuances in nudge design carry large implications in terms of acceptance, and thereby legitimacy, of nudge adoption [26], this study explores the effect of shifts in the design of nudges on public acceptance. Specifically, five nudge scenarios are evaluated, as well as one variation of each nudge in which an element of the nudge design is varied (see Fig. 1). The selected nudges were adapted from nudges that have been demonstrated in the literature to be promising from an effectiveness standpoint for promoting various healthy and/or sustainable food choices. All but one (nudge 4) can be classified as default nudges. For each of the nudges, the second variation is anticipated to increase acceptance.

Summary of five default nudge scenarios and respective variations examined

Q2. How do perceived effectiveness, perceived intrusiveness, and engagement in the targeted nudge behavior influence the acceptance of default nudges for promoting healthy and sustainable food choices?

This study investigates the influence of three mechanisms on public acceptance of the five proposed nudge scenarios and their variations. These mechanisms were selected based on the following two criteria: (a) they are highlighted in the literature as particularly prominent drivers of nutrition policy acceptance amongst the public; and/or (b) if found to play a role in acceptance of default nudges, they are actionable levers for improving the communication of default nudges to increase acceptance. The first mechanism, which captures the extent to which the public believes the default nudge to be effective at achieving the desired shift in behavior, has been found to be one of the strongest predictors of nutrition policy acceptance in previous studies [27, 28], including specifically for nudges to shift food choices [29, 30]. Perceived intrusiveness, or the extent to which people believe the default nudge to limit freedom of choice, is another salient mechanism that has been found to mediate acceptance of a range of nutrition policies [26, 28, 31]. Finally, this study examines the impact of self-reported engagement in the behavior that is targeted by each nudge, as this has also been found to mediate nutrition policy acceptance [6].